Case study: SS.I typographic redesign

Hello, TypeDrawers!

I'm very pleased to share with you all a project that I have been working on for months. I am interested in (a) receiving any feedback that the TypeDrawers community may have, but even more importantly, (b) just sparking some discussion around the topic of typographic systems and design for scholarly text.

A little bit of background:

I am a typographer. My father is a world-renowned expert on the psychology of school shootings and the prevention of violence in schools. For the past seventeen years, we have run the website School Shooters .info. Used by the FBI, the Secret Service, the Department of Homeland Security, hundreds of news outlets, and thousands of ordinary citizens, SS.I is the most comprehensive and trustworthy source of information on the topic in the world.

In terms of design, there are two distinct facets to the site: there is the website itself, and then there are thousands of pages of downloadable PDFs. These PDFs are really the heart of the site, and I will be focusing here on the design of these documents, which are meant to be downloaded and printed.

We first built the website in 2008. Since then, it has gone through several major redesigns and rebuilds. At the moment, ten years after our last redesign, we are again embarking on an overhaul of the site. We will be rebuilding it from scratch on a different platform, adding many new features and a wealth of new data. In tandem with this, I am redesigning and re-typesetting all of the documents that are exclusive to the site — that is, every document that we created ourselves, including scholarly articles, edited primary sources, information graphics, and so on.

If you visit the site now, you will see our soon-to-be-superseded design from ten years ago, both in the webpages and the PDFs. Our new design will be a drastic overhaul and will replace the somewhat lugubrious aesthetic with a fresh, clean, airy, more inviting look. (This was something of a revelation for me as a designer: just because the content is dark, that doesn't mean the aesthetic has to be! On the contrary, the power of design lies in taking such a serious resource and making it accessible and even pleasant to use for the many researchers who rely on it. The scholars and law enforcement folks who use the site don't need to be reminded of the horror of the subject — they just need to be able to do their work efficiently.)

I am now in the final stages of creating our new typographic style for the PDFs. I have learned a lot since our last redesign, and one of the things I have learned is about designing for unpredictability. This is the hardest typographic design project I've ever done, which is why I wanted to share it. Although I've worked on literary journals and similar series designs before, I have never yet designed for an application with quite so many unknowns. As a very small example, designing the opening of an article might seem trivial, until you realize that the article might have:

2. A subtitle, or not

3. An author, or not, or more than one

4. Any number of other contributors, such as translators, editors, etc.

5. Authors' affiliations, or not

and the style has to account for every possible permutation.

I have found this process fascinating, and I am increasingly interested in the idea of designing systems for application when the specifics of the text are unknown.

Anyway, as you can see if you compare the documents currently on the site to the manual I've linked to here, we had been using a fiddly and over-designed combination of Scala,* Calluna Sans, Trade Gothic, and Skolar. I have moved us to a single type family, Lyon. The website will also be going all Lyon, all the time. The various layouts used for different kinds of documents have been streamlined into a single layout for everything.

*One of the problems with Scala is that it didn't have the characters we require, such as Vietnamese accents. For such a popular face, it's surprising that the character set has never been expanded. But I was ready for an aesthetic change anyway.

I've taken the opportunity of the in-progress redesign to write our first-ever comprehensive typographic style guide. You can see a draft of the manual here. This aspect of the project alone has taken several months. The result is a 136-page guide to our new style. It has information about the redesign, highly detailed specs, a guide to using the InDesign files, and sample pages.

Although I have been designing books for more than fifteen years, this is the first time I have ever written out typesetting specifications in the traditional way. Since I set my own type, I have never needed to. But this manual is intended to be used by other typesetters in the future, so I had to learn how to write specs. The process was illuminating. Compiling the manual required me to check and second-guess every aspect of the design. Resources that were helpful for writing the specs include Richard Eckersley et al., A Glossary of Typesetting Terms; Rich Hendel, On Book Design; and Andrew Barker, "Backwards and In High Heels," in Rich Hendel, Aspects of Contemporary Book Design. I consciously included much more detail regarding the niceties of composition that a designer traditionally would, because the folks who will have to interpret these specs in the future are not necessarily trained compositors.

Perhaps that's enough of an introduction for now. I may yet write an article about this design process, so I don't want to go on here at too much length. On the other hand, I welcome questions, which may even help me decide what to include in an article.

Re the manual: the draft I have linked to above is, indeed, a draft. Please do not disseminate it. The ten documents that I have typeset so far in the new style, and which form the basis of the "Layouts" section, are currently in proofreading; this section will be updated once they are proofed.

Looking forward to wherever this discussion takes us!

Josh

Comments

-

And already I'm responding to my own post to mention a couple of points I forgot:

First, I had to invent a new system of naming style sheets to keep the hundreds of styles organized. I landed on a system in which each style is assigned a three-digit mnemonic code. (This is similar to a system used in theatrical lighting design, one of my other professions.) Styles can be assigned rapidly by typing in codes. I'm curious about others' approach to this.

Also, this project brought up a sort of philosophical query, as follows. We publish a great deal of writing by mass murderers, including journals, blogs, school papers, etc. A question that I find interesting is to what extent we are ethically/editorially/typographically compelled to emulate the idiosyncrasies of their writings. For instance, if a shooter writes "I HATE YOU ALL" etc etc, in full caps, are we obligated to print it in full caps for authenticity? Or is it better to "civilize" the text by substituting small caps? We used to do the former; I have now moved to the latter for this redesign. My thinking is that, just as I would not allow someone to shout hateful things in my home, I am not obligated to allow killers to shout on my page. But I could justify either approach and would like to hear others' opinions.0 -

Substituting small caps for caps seems to me to be a house style question, and totally ok as long as you are consistent, and you have chosen a typeface that has real small caps. If text in all-caps is a common thing, then the design and spacing of those small caps will be more of a consideration in your typeface selection.

2 -

Strictly speaking, the small cap glyphs should be X.c2sc, rather than x.smcp, to preserve the capitalization of the original text.

Another alternative is to use a typeface with a large x-height, so that the capitals don’t shout so loud, relatively speaking.2 -

First, to address your question about full caps in quotations. Violent speech, whether it comes from mass murderers or certain political candidates, should not be civilized by dainty typographic treatment. Let the violence come through—unmitigated. Anyone who reads these reports, which concern some of the most ghastly acts in our country’s history, has not come to them for comforting.

The style guide is so lengthy and detailed that it would take me nearly as much time to examine and digest it as it did for you to compile it. Who could remember and follow such a thing? I can, however, comment on a few things in the page samples, which begin on p. 105 of the PDF.

- I find the setting of small caps to be overly spacious. Also note the resulting distance between letters and punctuation. (See also p. 122.)

- The affiliation line below the author’s name should be smaller.

- The precis paragraph, set all in italic, would be easier to read in shorter lines. You might consider indenting it 1p6–2p0 both left and right.

- Numbered lists: indenting here would help a lot. Too much space between the numbers and the following sentences.

- The space between small cap subheads and the subsequent text is too large (same as space above). This raises a key issue about the vertical grid. Why do you care about its evenness? Why no half-line spaces, which I believe are what you really need? Look at page 118—it’s not good at all.

- The footers need better differentiation. (Maybe smaller and slightly heavier.)

- You need semibold; I’m afraid you can’t get away with using a single weight throughout.

I could go on, but I’m sure you get the idea. Hope that helps!

I think Lyon is an excellent piece of work, but I don’t like reading it. (How’s that for a back-handed compliment?) I find the line weight too even and the x-height too high (specifically, I find tall counters to be an impediment to long-haul reading). In the New York Times Magazine, where it’s used for text, I find it so oppressive that I prefer reading the articles online. There are better choices, in my opinion.

0 -

Hello, Scott-Martin!

Many thanks for taking the time to look at this. It occurs to me that I have several books on which you've worked on my shelves, including Paul Shaw's NYC subway signage book and The Eternal Letter.

Regarding the length of the manual: the intention is not really that any one person will read it straight through, but that it is there for reference when needed. The style is almost entirely recorded as InDesign style sheets for easy application. But some things cannot be automated. And, as it says in the manual, if InDesign is eventually superseded by some other tool, it will be necessary to have the designer's intentions recorded somewhere, independent of the INDD files. (My approach to documentation is loosely based on that of the Penguin Classics series style by Andrew Barker. I have learned a lot from him, including the utility of a centered layout when content is unpredictable.)

For seventeen years we have used a style that aligns with your point about violent speech, distinguishing typographically between primary sources and scholarly analysis. I've found, though, that this distinction is not always clear-cut and trying to honor it can lead to much case-by-case fiddling and result in apparent inconsistency. My current feeling, which is by no means the last word on the subject, is that typographically softening hateful speech is a sign of civility, a subtle hint that the scholars, and not the perpetrators, are in control. Our readers fully comprehend the enormity of the topic, even if we turn down the volume on the mic, so to speak. From a practical standpoint, adopting a single style for all forms of text supports more efficient typesetting, which matters when we have thousands of pages of material to set. But this remains a discussion in which I'm interested.

I like several of your suggestions, such as setting affiliations slightly smaller. I already have a smaller text size for notes etc. that may work well for this. I just need to see how the text-size sc for author names interact with the smaller u&lc.

About Lyon, I'm afraid we disagree. Have you seen it as used in the 17th edition of the Chicago Manual of Style? This may be the use that first caught my attention. We conducted a very thorough search for a new text face, and I'm pleased with this result. After using Scala for so long, I began wishing for a face with greater stroke contrast, which I find aids readability. This is one of the reasons, among many others, that we landed where we did.

Thomas and Nick, thanks for your observations. I use INDD's OpenType "all small caps" for sc, which preserves the underlying text casing.0 -

I use INDD's OpenType "all small caps" for sc, which preserves the underlying text casing.

Not necessarily, which is why I raised the issue.

I have on occasion coded <c2sc> as e.g.sub X by x.smcp

…with no X.c2sc, the reason being that one need only include one set of small cap glyphs in a font, and it does double duty for both <smcp> and <c2sc>.

IIRC, we have discussed this before at Typedrawers and there was a grudging consensus that this efficiency is acceptable.0 -

...0

-

InDesign has native PDF export (as do most environments nowadays), so there is no chance of the underlying text association to a cap rather than lowercase being lost.

That would require a scenario such as:

- print a PostScript file to disc

- generate PDF from the streamed PS file on disc, AND without the generating app having the original font, AND the print stream doesn’t have the full font either (this last common with OpenType CFF back in the day, but not TTF).

20–25 years ago, this was not super common, but reasonable to consider as a corner case. It particularly mattered to Adobe, who (1) were making OpenType CFF fonts only, (2) cared immensely about PDF being as bulletproof as possible as it was their format. As Adobe’s de facto OpenType evangelist for some of the early years, I pushed this idea.

Nowadays, it seems incredibly unlikely, and the loss sufficiently small, such that I would absolutely endorse going with a single set of small caps rather than two sets. If I was making a font specifically for Adobe, I might ask them about it first.2 -

If it was you that disagreed with my previous comment, Thomas, please note that I said “not necessarily,” and alluded to your previous opinion with “grudgingly.”

But thanks for clarifying!0 -

Thanks, all, for your comments. I'm going to be implementing at least one of Scott-Martin's suggestions and maybe more. I need to think through the ramifications of some of them. I welcome any additional feedback, thoughts, or questions from the community!0

-

Changes since I posted the draft above:

1. I've reduced the attribution lines in the title block by one point.

2. I've reduced the running foot text by a quarter of a point.

3. I've finessed the GREP styles for kerning upright delimiters against italic text to be more nuanced.

We're getting ready to start publishing documents in the new style. Any other notes?0 -

Joshua, I’m sure you’ve run across the old maxim, often attributed to William Faulkner, “In writing, you must kill all your darlings.” What this addresses is the stoicism it takes to be a good self-editor, the ability to get rid of a passage that seemed so wise or clever when you wrote it, but actually disrupts the flow of the story. You have to cultivate the ability to step back and become the reader.

Design is not at all different from that.

I think you got so caught up in making a set of style sheets that you neglected to become the reader, who cares only about how it feels to read a page, not about the measurements. It also seems that might have got caught up in D.B. Updike’s dictum about avoiding boldface types. You have to remember that Updike (like Bruce Rogers and even W.A. Dwiggins) came from an era in which bold versions of types were either not authentic to the original designs or were considered latter-day vulgarities. We no longer live in that era and such orthodoxies are no longer valid.

I think your design needs a good bit more work—more than just a nip here and a tuck there.

1 -

Scott-Martin, with the utmost respect to you and your fine work, I disagree. After some six months spent developing the style and scrutinizing the pages, and after typesetting, reading, and proofing some 300 pages of text set in the style, I am very pleased with it overall. I'm certainly open to critique and discussion — that's why I shared the work — but I find your comments a little too vague to be actionable. I might also add that after working on SS.I for seventeen years, I am very familiar with some of the specific and unusual problems that are unique to this project and that I have striven to address in the redesign. The avoidance of bold, and indeed of a sans or any secondary type, is part of a deliberate choice to make the style as aesthetically simple as possible. (You've suggested adding bold, but haven't explained for what or how it would help.) I wonder if you might not actually prefer the current style (see almost any article on the site for an example) to the one we are now developing — but the current style has many shortcomings and pitfalls that I believe I've now addressed satisfactorily for the first time. Regardless, my thanks for taking the time to share your thoughts.

0 -

Joshua, I think this has become too particular for a public discussion. Please feel free to contact me through my website if you’d like to discuss it further.

1 -

Hello, TypeDrawers community!

I just wanted to share that the new typographic style guide for School Shooters .info is complete, and we have started to publish documents in the new style.

The finished guide may be seen here.

Our first ten documents reset in the new style may be viewed here.

Perhaps some of the geekier typographer/typesetter types out there will enjoy looking through the manual, which contains, among other things, 40+ GREP styles for finessing composition, hyphenation, kerning, and other such matters. It may also serve as a sort of exemplar for other folks who are working on, e.g., designs for academic journals.

Developing this style has been the most complex and difficult typographic project I've ever undertaken — much harder than designing a book, no matter how complex, because the style must cope not only with known content but with unanticipated content to be published in the future. I've attempted to account for every typesetting need that might reasonably arise, while keeping the style devoutly minimalist. Indeed, I've discovered that typographic restraint is the friend of textual complexity.

My best to all of you as we enter this holiday season.0 -

Good morning, TypeDrawers denizens!

I'm not sure whether this thread has been of use to anyone, but just in case some other typographer out there is interested in tracking my progress on this project, I thought I'd share some more materials.

The latest mockup of the redesigned website can be viewed here. You can see my annotations, some of them typographic in nature, for our web developer. I think (I hope!) you'll agree this is a vast improvement over the current site.

Here is my workspace setup for typesetting our PDF files:

This is a two-monitor setup. On the lefthand monitor is the main InDesign window. Note the scripts at lower right for inserting commonly needed characters and strings of characters. On the righthand monitor are all the style sheet palettes. Style sheets have been assigned unique mnemonic three-digit codes and can be called up by number (using "Quick Apply") rather than by clicking through the nested folders. At lower right would be the MS for whatever I am typesetting — or, in this case, the photos of the journal whose transcript I am editing.

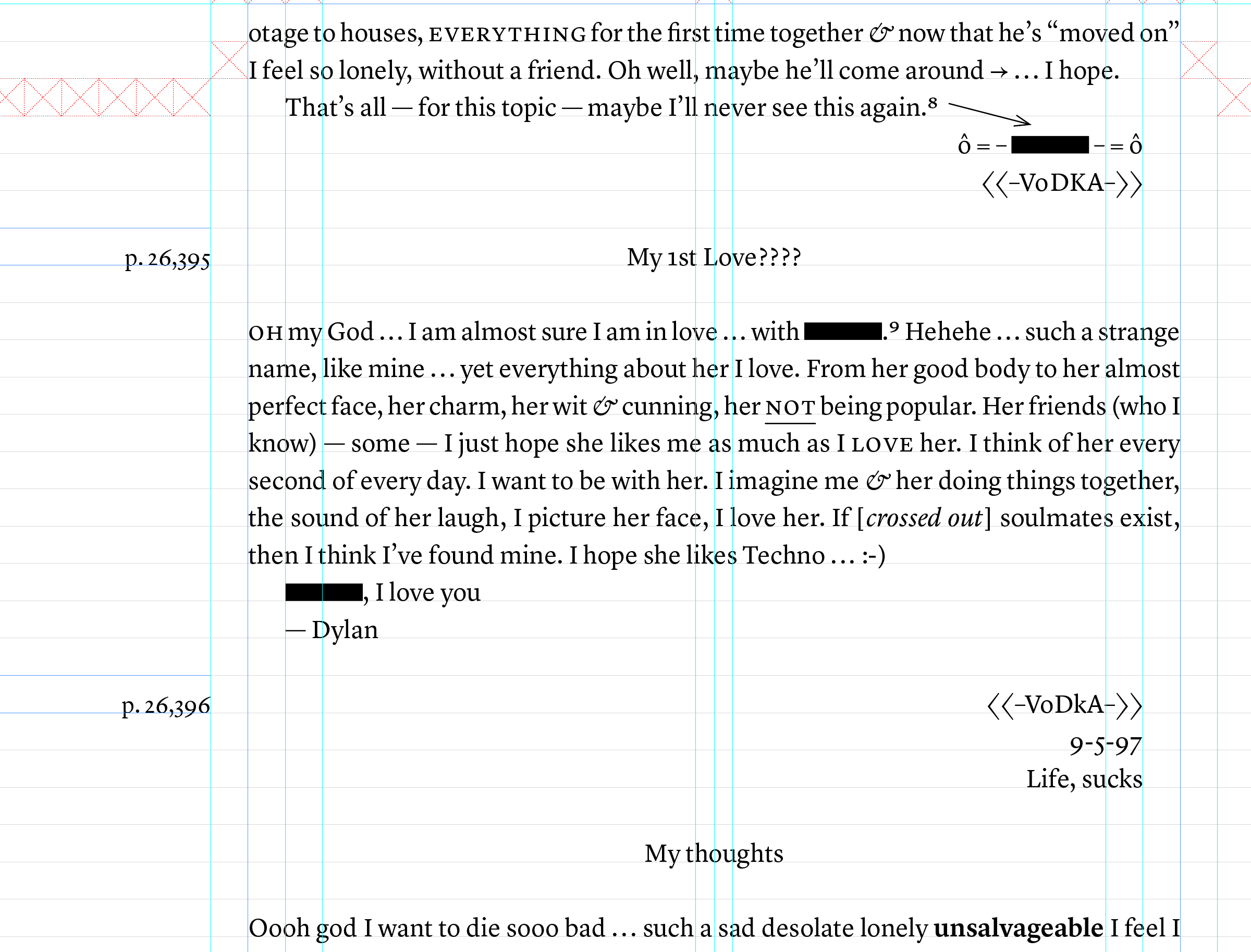

Other (possibly interesting?) screenshots of typesetting in progress follow. Much of what I typeset for this project consists of academic articles, but the images that follow are mostly of primary sources, which can present a host of typographic problems. (Content warning for profanity and offensive language.)

Some of our completed typeset PDFs can be viewed here.

The typographic style guide, of which I posted a couple of drafts above, will be getting some edits soon. Overall, our new style is working very well for us, but, as always, there are some contingencies I did not account for initially and other adjustments that come with implementation. More to come about that.

Happy Sunday, everyone.0 -

Joshua, I haven’t had time to dig into your questions, nor give feedback, but I wanted to let you know I appreciate your thoughtful effort for a very important cause. You may feel like you’re talking in an empty room, but I assure you people are reading (and will read) your posts on this project. Documenting your typographic process is valuable, and I hope you get a sense that folks will get something out of it, even if it’s not obvious now.11

-

Thanks, Stephen, that actually means the world to me. I had wondered whether I should stop discussing this, since I didn't sense any interest, but thanks to you I will keep posting updates. The current redesign has been over a year in the making; the new website is currently being engineered and coded from scratch, and there will be MUCH more to report in the coming months, I expect.

1 -

Today: experimenting with angle brackets.

In this case, angle brackets denote text in a handwritten journal that was added as an afterthought, between the lines. Note also my custom diagonal strikethroughs, set as embedded objects.

I sometimes refer to this sort of task as "forensic typography" — trying to capture every relevant feature of a source text with academic accuracy. (Yes, all the misspellings are in the original.)

1 -

I suppose one could get used to the angle brackets, and it is a reasonable choice.

I am wondering if superscript and subscript might work well for this as well? Though of course that would depend on the typeface having enough super/sub characters, which could be a problem.0 -

Hm, yes, didn't think of that. Thanks. I have seen this done in transcripts of letters. Will consider.0

-

This is a typographically fascinating project, btw. Thanks for sharing it!1

-

Long strings of embedded superscript text don’t usually work well. As well as disrupting the texture of the page, they mean significant text is set in tiny size that can be difficult to read.

I think the angle brackets are a good solution.1 -

Thanks, John — they are yours!

(We very seriously considered Brill for this project. I've been an ardent admirer of the family for years. Although we ended up using a different text face, I do surreptitiously crib glyphs from Brill now and then.)0 -

Today's task: identity assets for the website and fundraising items, such as T-shirts. Note the custom ty lig.

0 -

The angle brackets seem to sit a bit low in relation to the lines of text, and to the parentheses and brackets.

This is a fascinating project! The typographic challenges remind me a bit of Friedrich Forssman's typographic adaptation of Arno Schmidt's Zettel's Traum.

3 -

Indeed, the angle brackets are not a perfect match and are not aligned perfectly. But this relates to what makes this whole project so interesting: finding the balance between optimizing a specific instance of something, or a specific document, and creating a stable, simple, automated system of production for thousands of pages of PDFs. I would love to find brackets that are a better match for Lyon, and to finesse their alignment to perfection. And perhaps I will do just that. But that requires then writing new GREP styles for hundreds of style sheets in 150 separate InDesign files, and updating the typesetting manual, and redoing previously typeset documents, which will cause text to reflow and change pagination … If I find the perfect brackets, it might be worth it. (The floor is open for suggestions.) Might. At this stage, a very small change can be a lot of work.0

-

I'll take suggestions for text faces with more closely matched angle brackets, perhaps a tad narrower and with a larger swell (wider stroke) at the vertex than what I've shown here. I almost feel — in spite of not by any stretch being a type designer — that I could draw them myself, but I'm not sure I want to go that route.0

-

I find the ampersand a bit showy and misfitting, for what it’s worth.1

-

I was waiting for someone to say that! Hrm. Yes. Thank you. This is a product of my following the general principle (stated by Bringhurst and followed by various historical and early-twentieth-century typographers) of using only the ital ampersand, regardless of context. I have wondered if, in making a big effort to swing our aesthetic toward the refined and academic, I may have swung too far in this detail. It looks lovely in academic citations (Smith & Jones, 2015) but, yes, incongruous in primary sources. Again, my task is to find the balance that works for all the sorts of texts we publish.

Few people actually write ampersand characters; the author of the journal shown above made marks that look like plus signs. We had a discussion about whether this was semantically just a handwritten variant of the ampersand or whether it was a distinct character, a plus. Thus the subjective nature of transcripts.2

Categories

- All Categories

- 46 Introductions

- 3.9K Typeface Design

- 489 Type Design Critiques

- 568 Type Design Software

- 1.1K Type Design Technique & Theory

- 662 Type Business

- 868 Font Technology

- 29 Punchcutting

- 523 Typography

- 120 Type Education

- 325 Type History

- 78 Type Resources

- 112 Lettering and Calligraphy

- 33 Lettering Critiques

- 79 Lettering Technique & Theory

- 563 Announcements

- 94 Events

- 116 Job Postings

- 170 Type Releases

- 182 Miscellaneous News

- 277 About TypeDrawers

- 55 TypeDrawers Announcements

- 120 Suggestions and Bug Reports