Cursive

Cory Maylett

Posts: 253

I read an article in The Atlantic magazine saying that around two-thirds of so-called "Gen Z" students born in the U.S. can neither read nor write cursive. Apparently, cursive writing is no longer taught in U.S. schools.

Paradoxically, this inability corresponds with the recent popularity of script and handwriting typefaces. The article makes me wonder if these faces are the last hoorah of the final generation capable of reading them.

Paradoxically, this inability corresponds with the recent popularity of script and handwriting typefaces. The article makes me wonder if these faces are the last hoorah of the final generation capable of reading them.

2

Comments

-

And good riddance! I always hated cursive handwriting.Script typefaces are usually a great deal more legible than a real person's scrawl.2

-

Lots of 50s–70s cursive models in the US (the Palmer Method comes to mind) were ghastly ill-conceived adaptations of pointed pen, modulated stroke copperplate scripts executed by pencil, pen or other monoline technology. I remember being enamored with them at 6 years old and now embarrassed in hindsight.

I prefer italic-based methods taught by Gunnlaugur Briem and Nan Jay Barchowsky. I’m a bit biased toward Barchowsky. ☺

I prefer italic-based methods taught by Gunnlaugur Briem and Nan Jay Barchowsky. I’m a bit biased toward Barchowsky. ☺ But If I Ran The World, schools—or God forbid, parents—might, oh I don’t know, spring for some inexpensive double-ended Zig black calligraphy markers for their kids and let them learn humanist lowercase, then italic lowercase, then finally Roman uppercase, and learn monoline based on those models.

But If I Ran The World, schools—or God forbid, parents—might, oh I don’t know, spring for some inexpensive double-ended Zig black calligraphy markers for their kids and let them learn humanist lowercase, then italic lowercase, then finally Roman uppercase, and learn monoline based on those models.

1 -

A couple of years ago, I designed a book for 9- to 14-year-olds ("tweeners," as the publishing company called them). The publishers told me not to use any script or cursive handwriting typefaces. When I questioned them about it, they said they had received complaints about other books from parents who said their children that age could not read cursive writing. Subsequent focus groups, they said, confirmed it — most had great difficulty reading any script fonts.

I don't often use cursive anymore, but I found doing do very useful in university classes when taking notes. My mother, who went to high school in the 1930s, had wonderful handwriting and usually used a fountain pen. She said fountain pens were the norm in her Palmer Method classes @John Butler mentioned. I looked it up — ballpoint pens were too expensive for everyday use until the 1950s when the cost came down and became popular.2 -

I learned cursive in third grade and was forced to use it through eighth. In high school my teachers made many of us stop using cursive because our terrible penmanship was hard to read. When I started college professors told entire classes not to use cursive at all. So I basically wasted hundreds of hours practicing a useless skill that nobody in the real world cared about. Good riddance to cursive—teach children something that actually matters.

The downside is that in ten years all the beautiful OpenType script fonts that have been designed will disappear. But it’s worth the loss if children learn something useful.1 -

The life and fate of cursive is deeply ironic: The forms developed naturally from print forms through patterns of quick and messy handwriting, and then were seized by prescriptivism so that we could tell schoolchildren "learn these confusing shapes and duplicate them as neatly as possible." And of course it isn't about the shapes, it's about getting the kids used to following arbitrary rules and being judged. I remember when I was little, I was taught to draw looped ascenders, then the worksheets from another teacher the next year all said "NO LOOPS!", and it was clear to me even then that the lesson I was learning was not about penmanship.And of course some bastard had to invent the capitals, on purpose, just to make them equally challenging, as most of them don't connect and it wouldn't have happened naturally. Nobody can remember or agree on them. Nobody, not even those who still write cursive in everyday life, has used those cursive capital forms in reality since the design of the General Mills logo. I'm sure that if I searched the flood of script fonts it would take all day to find a Q that looks like a 2.As a designer, it is good to have more forms to work with, and it is dismaying to think the pool of them is shrinking as people become less likely to recognize them. I have noticed that the uniformity of online text has made younger people easily revolted by any perceptible deviation from the two or three fonts they are used to reading. It can seem like there's less room for creativity. But recognizing something is easier than replicating it, and people are more flexible than we give them credit for, so I suspect that for a good long time, people will still pick stuff up from context and grow up to be able to read script even if they were never taught it formally.It's important to remember that when you hear popular complaints that "kids aren't learning cursive anymore", it still isn't really about cursive.

2 -

in this time when the text message replaces the written note, typing is the used skill. I am nearly 80 so handwriting was a strong part of my early life. It is a warm memory of a different time and deserves its place in the archives of history but is not needed for school children today to learn.

0 -

This could explain some of the badly designed script typefaces I've seen lately, which look as if they were designed by people not very familiar with script forms, especially the capitals.6

-

I couldn’t disagree more. Clearly the model proposed is important (John Butler underlines the problem with many "cursive" models which were used in schools along the last century), but the act of writing itself involves matters that are way beyond practical problems, be them more or less technical.Chris Lozos said:in this time when the text message replaces the written note, typing is the used skill. I am nearly 80 so handwriting was a strong part of my early life. It is a warm memory of a different time and deserves its place in the archives of history but is not needed for school children today to learn.

And to answer the question you raise: I have never stopped to take notes on paper. This comes even before considering the question of educating children at handwriting.1 -

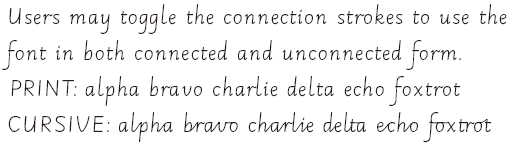

Many of the recent script fonts resemble connected handwritten printed letters more than the cursive I learned as a child. Very few of the newer cursive fonts use the "General Mills" G or a Q that looks similar to a 2.

I wonder if the recent popularity of script fonts is due to nostalgic associations of cursive handwriting with the handmade homeyness of simpler times. Head to the craft-oriented sites that distribute fonts, such as Creative Fabrica, and seemingly most of their fonts are trendy imitations of cursive writing.

I wonder if the popularity of script fonts will bottom out as teenagers turn into adults who have trouble reading them and little personal connection to them.4 -

John makes a great point that “cursive” has many meanings. It could mean the loopy scripts of the Palmer method (19th-century business hand), or it could be the much simpler methods derived from Rosemary Sassoon’s research. The “script” category in typefaces have even broader definitions. It’s specifically the spencerian and other antiquated forms (and the joining lowercase ‘r’ and ‘s’) that are most in danger of extinction.2

-

This page from Briem’s guide adds sheds a lot of light on what makes the difference between copperplate and italic writing: the tool. The practical purpose behind loopy capitals was news to me! “To get the ink flowing, entry strokes were added to copperplate writing.”

4 -

That is also the main point. Children need to learn from models that actually allow them to familiarize with the basic forms. The idea of using complex historical scripts, largely adopted across the XX century, was probably not the best choice.Stephen Coles said:John makes a great point that “cursive” has many meanings. It could mean the loopy scripts of the Palmer method (19th-century business hand), or it could be the much simpler methods derived from Rosemary Sassoon’s research. The “script” category in typefaces have even broader definitions. It’s specifically the spencerian and other antiquated forms (and the joining lowercase ‘r’ and ‘s’) that are most in danger of extinction.

For cursive forms, models based on chancery cursive as used by Sasson and Williams are the best.0 -

Well, cursive — historically — *is* "handwritten printed letters", in the sense that cursive forms arise from the need to write forms quickly. The carolingian minuscule, and then the subsequent cursive forms, all stem from the need to write quicker the capital forms.Cory Maylett said:Many of the recent script fonts resemble connected handwritten printed letters more than the cursive I learned as a child. Very few of the newer cursive fonts use the "General Mills" G or a Q that looks similar to a 2.

So while historical models specific of a given time, context or writing instrument can come and go, or be prone to use oscillations or fashion, the need to write effectively will always individuate forms that stem from the need.

Surely many historical "learned" cursive models have little to do with the "handmade homeyness of simpler times”. In my opinion Copperplate models or the ones you mention had varied impact on our generation (born between 1960s and 1970s) already. As an italian I learned at school the cursive forms of these "not so ideal" models, but then spontaneosly integrated — by observation — elements of our own chancery cursive. And for the capitals I ended up with the simpler, more effective form, adapting them to the need of writing quickly and effectively that I mentioned.

This does not erase the need to teach models which can aid children to find the best way to write.0

Categories

- All Categories

- 46 Introductions

- 3.9K Typeface Design

- 489 Type Design Critiques

- 568 Type Design Software

- 1.1K Type Design Technique & Theory

- 662 Type Business

- 868 Font Technology

- 29 Punchcutting

- 523 Typography

- 120 Type Education

- 325 Type History

- 78 Type Resources

- 112 Lettering and Calligraphy

- 33 Lettering Critiques

- 79 Lettering Technique & Theory

- 564 Announcements

- 95 Events

- 116 Job Postings

- 170 Type Releases

- 182 Miscellaneous News

- 278 About TypeDrawers

- 55 TypeDrawers Announcements

- 121 Suggestions and Bug Reports