White on black

https://www.daltonmaag.com/library/darkmode

Personally, I think dark mode interfaces are a little overrated to begin with. Setting that aside, I'm wondering whether it makes much sense to design special typefaces for it. Is the white on black thing really an optical illusion, or is it about how displays rasterize white vs black pixels? Does it make sense to adjust anything other than weight? How about ink traps?

Just some thoughts, curious to hear your opinions.

Cheers,

Jasper

Comments

-

To my eyes, reversed type needs to be a tad bolder. That means a slightly bolder weight drawn in black. For wayfinding, glyphs are typically a bit bolder than text on paper reading. Glare in backlit type (tramsmitted light) acts a bit differently than ink trap technique. Modern day printing is less affected by ink squeeze than it used to be 50 years ago. Letterpress is rarely used.

6 -

It is called the irradiation illusion and happens off-screen too (it's an important factor in signage design).The only necessary optical adjustment is to make white letters on a dark background a little lighter in weight, which is precisely what Dalton Maag's typeface does when you look at the little interactive axis slider on the website you linked. Seems a little gimmicky perhaps, because there's already a weight axis which does the exact same thing, but it could possibly be useful for UX designers who make a website with darkmode toggle, so that all text will adjust its weight by a predefined amount.Come to think of it, besides reduced weight, slightly increased tracking may be good for dark mode, but DM's font doesn't seem to do that.4

-

Actually... I do recall reading an article postulating that in the case of screens, the issue is not limited to the irradiation illusion, but begins on the stage of rendering (and has to do with subpixel smoothing). I can’t find it right now, but a quick test (under Windows, Firefox)...

If you consider the color fringes on stems of letter d or h...And I mean, even when evaluating the weight of the glyphs zoomed in, I am consciously inclined to consider the color fringes as part of the stem in the white-on-black glyphs, but disregard them in black-on-white.

If you consider the color fringes on stems of letter d or h...And I mean, even when evaluating the weight of the glyphs zoomed in, I am consciously inclined to consider the color fringes as part of the stem in the white-on-black glyphs, but disregard them in black-on-white.

Of course, the exact rendering will vary and depend on the renderer, font size, etc., but I do sense that there’s something funny overall and this was messed up at some early design stage a long time ago.

4 -

They wanted to avoid reflows.Matthijs Herzberg said:Come to think of it, besides reduced weight, slightly increased tracking may be good for dark mode, but DM's font doesn't seem to do that.

From the overlay at the Dalton Maag, it's apparent that they haven't merely mechanically emboldened the dark mode cut (in Glyphs app terms, just run an Offset Curve filter on everything), but TBH I wonder if anyone could actually perceive the difference between hand-drawn and offset-filtered. Like I wondered with the similar selling point of "grades." Subtleties on top of subtleties.1 -

It’s all quite simple, really. Look through your various offerings and identify some types you think might work well in dark mode, then test them. When you find one, give it a snappy new name and describe it as “especially engineered for dark mode.” Voilà, you’ve got a new product, especially engineered for the gullible (don’t say this out loud, as some will think you've joined the Dark Side).

“Dark Mode” sounds rather ominous—and it is for those of us with color-vision issues. It’s curious that Dalton-Maag was first in line with such a product. Protanopia, a common form of color-blindness is also known as Daltonism.

0 -

They mention tracking in the fourth image of the Instagram gallery, but not on the website.Matthijs Herzberg said:Come to think of it, besides reduced weight, slightly increased tracking may be good for dark mode, but DM's font doesn't seem to do that.

The font is nice, and a dark appearance axis is certainly a feature that gets people talking about a new typeface. I know people serving different fonts to Mac and Windows devices because of the display differences, and iA Writer tweaked its fonts once Retina/high resolution iPads became available, so a dark appearance variant does not seem unreasonable.1 -

Don’t see any reasons for sarcasm just because a technology allows to make a potentially useful feature easily.Scott-Martin Kosofsky said:“especially engineered for dark mode.”

0 -

To avoid potential confusion: the instagram post is from FontFabric, the link is from Dalton Maag.

Thanks for that link! great see that Von Helmholtz is still relevant todayMatthijs Herzberg said:It is called the irradiation illusion and happens off-screen too (it's an important factor in signage design).The only necessary optical adjustment is to make white letters on a dark background a little lighter in weight, which is precisely what Dalton Maag's typeface does when you look at the little interactive axis slider on the website you linked. Seems a little gimmicky perhaps, because there's already a weight axis which does the exact same thing, but it could possibly be useful for UX designers who make a website with darkmode toggle, so that all text will adjust its weight by a predefined amount.Come to think of it, besides reduced weight, slightly increased tracking may be good for dark mode, but DM's font doesn't seem to do that.

Looking at those examples, it seems to be a perceptual thing indeed, at least up to a certain extend.

Instead of decreasing weight and increasing tracking, it seems to me that the best solution would be a kind of offset curve filter like @Craig Eliason was alluding to, which would at once decrease the stroke thickness and increase the space between letters. Basically, it's countering the optical 'bleed' from white into black.Adam Jagosz said:Actually... I do recall reading an article postulating that in the case of screens, the issue is not limited to the irradiation illusion, but begins on the stage of rendering (and has to do with subpixel smoothing).

That's also my impression, and your example appears convincing enough to me! I would also argue that this rendering effect is probably larger than the illusory optical effect, especially at smaller sizes (ever tried to read white on black text on a Mac?). But why would this be the case? And shouldn't this be fixed at the rendering level, rather than at the font level? Or is that wishful thinking?

Yes, it could be useful in some circumstances. But to me, 'engineered for dark mode' does have a slightly gimmicky ring to it. As if this is some high-tech solution. In reality, it seems more like a somewhat clunky (but useful) solution to an odd rendering problem.Alex Visi said:Don’t see any reasons for sarcasm just because a technology allows to make a potentially useful feature easily.

2 -

My sarcasm (a style of humor to some) was not without an underlying truth: this is not an issue requiring a technological solution, but rather a visual condition requiring appropriate aesthetic choices. There are design qualities that allow type to work well in “reverses” (the U.S. term for light type on dark backgrounds): sufficiently open counters, somewhat looser spacing, and thin lines that won’t dissolve into noise in small sizes. Thousands of existing fonts have those characteristics, and thousands more could have them with minor tweaks, such as tracking, made by their users.

What’s made this possible and simple are the recent generations of high-resolution screens (unimaginable even ten years ago) and recent developments in offset printing technology that are no longer as beholden to issues of trapping as they were earlier. It’s my opinion that what Dalton-Maag has done is no more than a marketing gimmick. At best, they are offering a choice that works for people who are unable to make such simple decisions on their own.

0 -

“They're arguing that type looks different white on black”

The tone here makes it sound as if this is debatable or uncertain. It is a well-known and well-documented visual effect. And it isn’t some vague kind of “different”—it is primarily a difference in apparent weight.

The most entertaining thing is, white on black text needs to be:

- heavier/bolder for printed type

- lighter/less bold for type on light-emitting screens (which does not include e-ink)

5 -

The problem is not that some type doesn’t work well on black, but that any type works differently on black and white. And the difference can’t be adjusted with just letter spacing for two reasons: it doesn’t correct the optical difference in weight; it leads to reflowing of text.Scott-Martin Kosofsky said:There are design qualities that allow type to work well in “reverses” (the U.S. term for light type on dark backgrounds): sufficiently open counters, somewhat looser spacing, and thin lines that won’t dissolve into noise in small sizes. Thousands of existing fonts have those characteristics, and thousands more could have them with minor tweaks, such as tracking, made by their users.

2 -

The weight axis does not do the exact same thing as their "Darkmode" axis: weight affects advance widths; "Darkmode" does not. "Darkmode" is like what is often referred to as "grade": small adjustments in stroke weights to compensate for medium or context conditions that affect apparent weight without affecting advance widths.Matthijs Herzberg said:...The only necessary optical adjustment is to make white letters on a dark background a little lighter in weight, which is precisely what Dalton Maag's typeface does when you look at the little interactive axis slider on the website you linked. Seems a little gimmicky perhaps, because there's already a weight axis which does the exact same thing...3 -

Jasper de Waard said:

That's also my impression, and your example appears convincing enough to me! I would also argue that this rendering effect is probably larger than the illusory optical effect, especially at smaller sizes (ever tried to read white on black text on a Mac?). But why would this be the case? And shouldn't this be fixed at the rendering level, rather than at the font level? Or is that wishful thinking?Adam Jagosz said:Actually... I do recall reading an article postulating that in the case of screens, the issue is not limited to the irradiation illusion, but begins on the stage of rendering (and has to do with subpixel smoothing).Funnily enough there's a snippet of CSS that is supposed to lighten the apparent font weight and fix the issue across browsers on macOS (and macOS only, the rendering in all browsers on Windows is unaffected):-webkit-font-smoothing: antialiased; -moz-osx-font-smoothing: grayscale; text-shadow: 1px 1px 1px rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.004); text-rendering: optimizeLegibility !important; -webkit-font-smoothing: antialiased !important;

And I suppose it’s too late at this point for anyone to really “fix” anything because backwards compatibility. But also laziness.

3 -

I feel like a cop saying “move on, nothing to see here, folks.”

Please note that I said “thousands of existing fonts,” not all of them. It’s been estimated that that there are about a quarter million individual fonts on the market, so “thousands” does not necessarily denote a very large percentage. Of course fonts work differently on black or white, but that doesn’t mean the situation requires fonts designed specifically for one purpose or the other. There are plenty of existing fonts that could benefit from dark mode—a matter of taste, not a matter of fact. It’s also a situation in which variable fonts could find good use. It’s interesting that Dalton Maag chose for its demo an ultra-bold sans serif set in the style we used to call TNT (tight, not touching). I’m pretty sure that this involved manual kerning, not the font’s natural spacing. Look at the differences in “tive.” So what?

I’m afraid that some people who work exclusively in type design have lost their connection to people who work in graphic design and have little idea how design decisions are made in real time. I can’t imagine any (or many) graphic designer(s) buying a specific font just to work in “dark mode.” Instead, they’d try the fonts they had until they found one that was satisfactory. It’s just not that big of a problem, though in the case of proprietary corporate fonts, some special versions might be useful. It depends on the design of the type and the design of the graphic work.

In the beginning of the offset era and into the era of photo-lettering, a number of type suppliers offered “half weights” for the purpose of printing reverses, as the trapping inadvertently reduced the letter weight in a noticeable way, much more so than in the offset printing of today or on the screen. By the late 1980s, Adobe Illustrator, and to a lesser extent Quark XPress, allowed users to adjust the trapping strokes as they saw fit, but by the later 1990s, the newer raster image processors took over that function. As the register accuracy of modern printing presses became nothing less than astonishing, visible losses from trapping have nearly vanished.

1 -

The reason for that tone is that I was somewhat skeptical of the extend to which this is a visual effect (i.e. something to do with the way the eyes and brain perceive things), as opposed to a more technical effect, caused by rendering engines and printers. It now appears to me that it is both.Thomas Phinney said:“They're arguing that type looks different white on black”

The tone here makes it sound as if this is debatable or uncertain. It is a well-known and well-documented visual effect. And it isn’t some vague kind of “different”—it is primarily a difference in apparent weight.

The most entertaining thing is, white on black text needs to be:

- heavier/bolder for printed type

- lighter/less bold for type on light-emitting screens (which does not include e-ink)

Your comment regarding prints vs screens is interesting. It makes me think that an important contributor to the effect is ink bleed in print, and some form of pixel bleed (for lack of a better term) on screens, as demonstrated neatly by @Adam Jagosz. Both of those effects are separate from the irradiation effect as described by Von Helmoltz.1 -

As far as I am aware, this can be perfectly adequately explained by the physical properties of light and ink in the respective imaging models. I do not see any reason to assume some additional factor peculiar to the eyes/brain/perception, although specific testing would be needed to rule it in or out.

Yes, ink bleed is the issue for reversed type in print. And on screen, dark mode compensation is essentially dealing with light bleed.

1 -

Maybe you're right. It would make for a nicely concise explanation.

On the other hand... Von Helmholtz (the guy who coined the term 'irradiation illusion') is a scientist that is still held in incredibly high regard, a pioneer in the field of psychophysics (a field of science that is very close to my own) whose work has stood the test of time very well. He died a couple years before the invention of the Cathode Ray Tube (the earliest digital display, I believe), so he would have had to perform his research without a digital display. Therefore, I was operating under the assumption that the irradiation illusion applies not just to light-emitting surfaces, but is a more general (indeed, truly perceptual) phenomenon. But to be sure I would have to read his work on the illusion. Will report here if I ever get around to it!

At the risk of getting too technical: I could think of a rather simple neural cause for the irradiation illusion. Light excites neurons (or rods and cones, which are essentially neurons that specialised for light sensitivity in our eyes), the absence of light does not. This activity spreads (neural bleed?), so that a light surface spreads out onto the darkness around it, and a dark surface is encroached by the light surface around it. At the end of the day, whether we are looking at paper or a digital display, what we see is light entering the eyes.

With all of this said: I'd wager that ink bleed and 'light bleed' play a larger role than the irradiation illusion when it comes to design. Which is why referring to the irradiation illusion in the context of dark-mode interfaces to me has an air of over-popularised science to it (we take what scientific terms we can use and ignore the rest).2 -

Having now read about the irradiation illusion, I expect that it would increase the perceived weight of "reversed" type regardless of the display medium. And it definitely predates light-emitting electronic displays, as Galileo also wrote about it.

So, I will grant that as given, that some of this is specific to eyes and some is based on the media. Which is interesting, and gives us a good reason not to ever try to compensate just by measuring physical phenomena. Conveniently, AFAIK just about everyone trying to compensate for such factors is doing it based on human perception of when things look the same across the conditions in question. So regardless of the causes, the same testing can get to the right answers.

Additionally:

- the effect of reversed type in print at text to modest display sizes is still to make the type look thinner, even with fairly good printing quality and paper

- this is true despite the fact that the irradiation illusion actually has a countervailing effect against the thinning of reversed type in print

- therefore one can reasonably conclude that the irradiation illusion is weaker than the effect of ink bleed, for reversed type in print, under such conditions

Contrariwise, the irradiation effect would presumably have some amplification effect for the “light bleed” of reversed type on screen.

I would be fascinated to learn use cases for why it might be helpful to know how much is “physical” vs “human perception” aspects of all this, vs just knowing how much compensation is helpful. I suppose if we had robots whose perceptions did not have these same limitations of our visual system, that would be one case. Other ideas?1 -

too many variables2

-

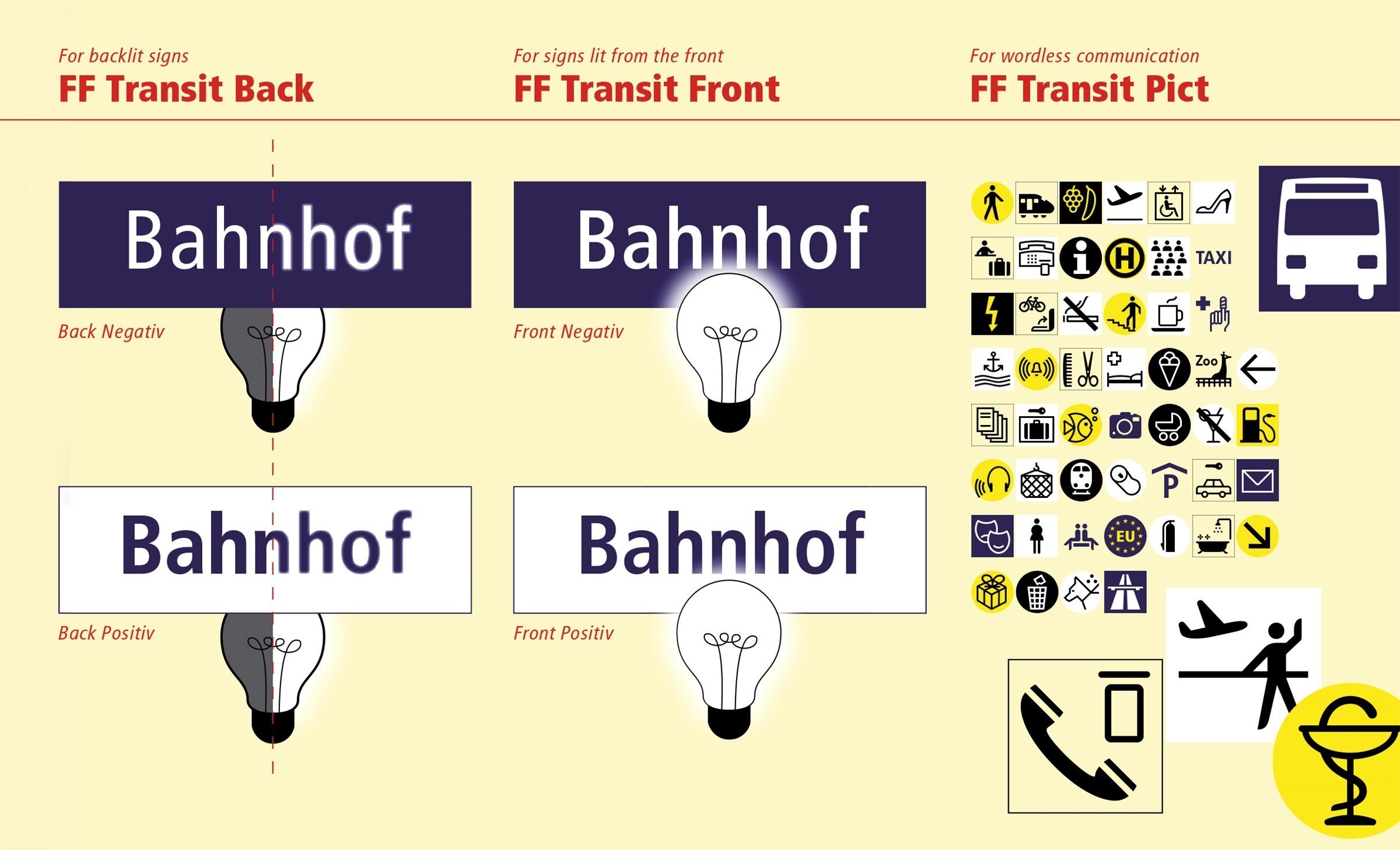

As mentioned above, this is well-known, documented and applied in analog signage design, compare FF Transit (1993) with styles for front-lit positive and negative as well as back-lit positive/negative text. So not only a phenomenon of screens, but rendering technology adds another fun layer to it. I find it quite useful.

2

2 -

I’m afraid that some of you are writing about conditions that no longer exist and are quoting outdated sources, especially in regard to printing.

What was described above as “ink bleed” has a proper name that better describes the condition: “dot gain.” Back when printing plates were imaged by photographic film intermediaries (negative or positive), the exposure had an inherent propensity to shape and size distortion. This was further exacerbated by the “crushing” of the dot in the “offsetting” of the image from plate to blanket. But as film was eliminated from the process in favor of digital direct-to-plate imaging in the 1990s, a major source of the distortion was eliminated, and with it a considerable amount of the dot gain. Other factors influence dot gain as well, specifically ink formulation and the dimensional stability of paper. But over the next two decades, raster image processors (RIPs) and press stability improved enormously, so that dot shape algorithms could compensate for a variety of variables, accommodating specifics of paper and ink formulations—and even climactic conditions. On the high-quality presses of today, dot gain is close to non-existent, well under two percent on most coated stock (as opposed to 20+% in the old days)—an amount that is pretty much imperceptible. This applies to reverses, so there is no need to make type to accommodate it and it would stand to reason that any specific need to adjust for the visual phenomena of white-on-black type should be made manually according to the specifics of the design elements (type size first among them).

If all you know of offset printing is the kind of low-price, gang-run services one orders online, you might still find sloppy work that gives the appearance of dot gain, but is actually other kinds of deficiencies. You might also keep in mind that the optics of the latest LED and OLED screens have been improving constantly and, as such, are moving targets that might defy making types specifically for black-on-white type.

0 -

This sounds pretty condescending and mansplaining, Scott. Don’t know if you notice. There are more cases than just “dot gain” where ink can bleed from a printing form. And there are other printing processes than offset where the former and the latter can be the case. There are also many different materials and inks one can use – on purpose – so you assuming everyone who talks about this topic is only knowing “low-price, gang-run services” is really strange.I take it you are not using Dark Mode for apps or websites on your computer or mobile devices, otherwise you’d know that the not-reflowing-part is crucial and the design application real. If maybe not dead crucial. Thanks for being more tolerant of different lived experiences and opinions.1

-

Apart from ink leaking into un-inked areas and human perception, there is also the physics of light and optics. Erik van Blokland gave some insightful talks on the subject. In the sense of light leaking into dark areas as rays get reflected from a white or bright surface, making the dark object appear smaller and more blurry. And the other way round.

3 -

Sorry to seem overbearing, Indra. (Mansplaining, ouch!) What I had read in a number of the above posts appeared to describe either the printing reality of ±25 years ago or poorly printed items of the present. I suspect—perhaps incorrectly—that I’m one of the few on this board who has decades of hand-on experience in both pre-press and press operations, large and small. Indeed, there are all kinds of printing materials and inks and processes; I was referring to the ones that are experienced daily by billions of people.

You are correct in assuming that I am not using dark mode on any of my screens. It’s for a very good reason: I am a protanope (a form of color deficiency). For anyone with the any of the three major forms of color deficiency—8% of all men and 0.5% of all women—dark mode is a perilous place, not so much for white on black as for colors on black, especially reds, which can become invisible or unbearable. (Helmholtz vibrations on steroids.) It’s a minority problem, for sure, but a minority of more than 300 million people worldwide. We don’t have a lobby group to campaign for our rights—yet!

I don’t think the typography of reverses/dark mode is a non-issue, but rather that, in regard to print, the solutions exist already. As for the re-flow issue in dark mode on screens, I’m afraid the matter is above my pay grade.

1

Categories

- All Categories

- 46 Introductions

- 3.9K Typeface Design

- 490 Type Design Critiques

- 569 Type Design Software

- 1.1K Type Design Technique & Theory

- 663 Type Business

- 868 Font Technology

- 29 Punchcutting

- 528 Typography

- 123 Type Education

- 326 Type History

- 79 Type Resources

- 112 Lettering and Calligraphy

- 33 Lettering Critiques

- 79 Lettering Technique & Theory

- 563 Announcements

- 94 Events

- 116 Job Postings

- 170 Type Releases

- 182 Miscellaneous News

- 278 About TypeDrawers

- 55 TypeDrawers Announcements

- 121 Suggestions and Bug Reports