Type and The Star Chamber

Deleted Account

Posts: 739

I was rambling on my mind Monday when I asked myself, "when was the first font specimen anyway?" Searching found William Blades book on early specimens of England, which also has one possible answer to my original question, 1616. But as I read through Blades, I found the Star Chamber's law limiting the English type industry to, like 16 people and 4 foundries. Does anyone know what brought this on?

0

Comments

-

Not the Ratdolt showing from 1486?0

-

Have you tried searching the catalogues of the National Archives? These include records of Star Chamber proceedings:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/catalogue/search.asp1 -

Sorry, I, I meant to say specimen book. There are quite a few showings, according to Blades, including some indication of the primitive state of marketing fonts, where no mentions were made of where to get the product. My guess here, is that the early showings might only have been delivered personally, or used for display where they were sold?

K, I have not read the proceedings of the Star Chamber. I'm not sure they would uplift my spirits It's just one thing: what event, or series of events, made them try to, or think they could, stop the English from being type founders? It didn't work, obviously, only lasting four years, I think. 0

It's just one thing: what event, or series of events, made them try to, or think they could, stop the English from being type founders? It didn't work, obviously, only lasting four years, I think. 0 -

Power corrupts, absolute power corrupts type completely? A brief search yielded nothing but the prospect of many hours reading, which while tempting I sadly cannot currently justify, and as you point out could prove disheartening!0

-

David, this might interest you, particularly pages 39–48. archive.org/stream/briefhistoryofpr00hamirich/briefhistoryofpr00hamirich_djvu.txt1

-

It was part of a general effort to control the publishing trade, involving also licensing of books, limiting the number of printers and apprentices, and regulating both importation and domestic distribution.

Limiting the number of suppliers of type strikes me a similar to efforts to control access to typewriters in 20th Century totalitarian regimes.1 -

It was standard practice that guilds would regulate and control their trades.

Further regulation by rulers was a way to manage (i.e. censor) the publication of dissent, as were newspaper taxes.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Areopagitica1 -

Thank you all for your wonderful and insightful posts and links! Yes Nick, 'twas common practice for guilds. For the state to set such a small limit... And the Areopagitica, as I was taught, is the first document of the American Revolution.

Karl and James, Thanks those were great reads. John, that they had control over the publishing trade, you are right on, it being so small, and crappy, and through the Tudors, they didn't have many readers. But the control turned to oppression when foreign printers came and then the writers couldn't be controlled.

Underlying English law then, I did not know, is that groups of workers not functioning as part of a state-sanctioned company were a criminal conspiracy. And one could be punished for printing a business card much more severely than having your disk eaten by coke. The control of writers lasted until the civil war, with parliament no longer willing or able to control the opposition writers, as the monarchy had to, and the church relatively too fragmented to do more than control the more threatening fringes, like e.g. the Puritans, who eventual won out on the platform promising god on the side of all printers, even atheists, and government in the business of printing everything, with regulation of practically nothing.

If I got that seriously wrong just hit the disagree button and I'll keep trying. I got on to this, because one of those conferencing organizations called to ask if I had any ideas. I started talking about my experiences participating in the first wave of democratization in publishing as it ran through Spain, Central and South America and then Eastern Europe and Russia, followed by the wave of democratization in type development along a similar course. This got them very excited, but I realized I only have a vague notion of the details of what happened from Caxton to the Declaration of Independence, which I wouldn't want to miss.

But now my research has become much more interesting to me intellectually than any presentation I'm interested in giving.

0 -

Indra, I guess that is another possible answer. What I was thinking of for the criteria of a specimen book, was not clear.0

-

David, not about type, but perhaps relevant to you as a history of the democratization of copyright in publishing: The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period, by William St Clair.

http://www.cambridge.org/gb/knowledge/isbn/item1164213/?site_locale=en_GB

At any rate, one of the most astonishing books I’ve ever read.

I was particularly impressed that his method of quantitative analysis offers a very different picture of literary culture than the traditional canon—which corresponds (albeit loosely) with my perspective on the canon of design history.0 -

Ordered, thanks!0

-

David, I think your summary is pretty fair, excepting perhaps the bit about the Puritan platform. I don't think the Puritan party had a uniform policy on freedom of the press, and Milton's Areopagitica, while of immense lasting importance, can be seen as a minority, or individual, position when it was first published. It did not persuade the mostly Presbyterian parliament to whom it was addressed to alter censorship regulations. The fact that it was published at all may be indicative of the instability of the time -- the height of the first civil war --, rather than parliamentary policy.

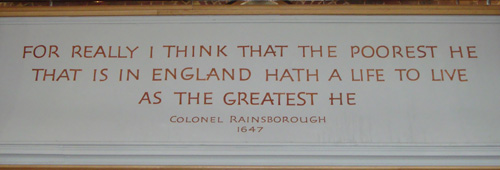

I recently read The Putney Debates of 1647: the army, the Levellers, and the English state, which includes an interesting account both of the sheer volume of pamphleteering and ephemeral printing during that period and what seems to have been an effective 'media blackout' with regard to the debates themselves. Like Areopagitica, the Putney debates are now considered to be hugely significant; at the time, very few people even knew that they had taken place.

____

On the subject of the Putney debates, here is an image of the painted inscription now in St Mary's church, where the debates took place. 0

0 -

John, thanks for the review.

"about the Puritan platform", I mean their eventual platform in America. The congregations had fled by the 1630's I thought, to the Netherlands and later New England. So before either Areopagitica or Putney, which I'm trying to read now, they had found relative freedom of the press for themselves.

0 -

Ah. Gotcha. I'm afraid my knowledge of Puritanism is mostly limited to England and Scotland.0

-

...and mine to a girl from high school...3

-

Coincidentally, this week's edition of In Our Time on Radio 4 concerns the Putney Debates. The programme doesn't deal with freedom of the press, but does give a good impression of the vibrancy of the pamphlet culture of the time, and there's a mention of something that strikes me as an excellent example of print as political talisman: the wearing of a pamphlet in one's hatband as a protest.

[If the link doesn't work after a week, check the In Our Time archives.]0 -

A "pamphlet" was new then right? This form of (cheap) publication didn't really exist before the combination of paper and letterpress print?0

-

Yes, pamphs were too big to fit in hatbands.0

-

Yes, this form of publication is directly associated with the development of letterpress print, although I probably wouldn't characterise it as 'new' in the context of the 1640s: there's an explosion of non-book print material in England earlier, much of it associated with the religious disputes of the Henrician, Marian and Elizabethan periods.

Evelyn Waugh's biography of St Edmund Campion has a fascinating section on the secret printing and distribution of Campion's Decem Rationes in 1581. The Jesuits had managed to set up a clandestine press at Henley, and conspired to have 400 copies of Campion's pamphlet left on the benches in St Mary's church, Oxford, on the day of the university Commencement service. Given the sensation this provoked, and the renewed government efforts to capture and execute Campion that it inspired, I suspect this kind of thing is directly associated with the Star Chamber efforts to control access to printing and typesetting technologies.

The 'Levellers' of the Civil War period produced pamphlets at an extraordinary, blog-like rate. I've got a collection of them published by Cambridge in 1998. They have magnificent titles—A remonstrance of many thousand citizens (Richard Overton, July 1646), An arrow against all tyrants (Richard Overton, October 1646), Gold tried in the fire (William Walwyn, June 1647), England's new chains discovered ('Freeborn John' Lilburne, February 1649)—and Overton penned what I think is the greatest address to members of parliament ever made:We are well assured ye cannot forget that the cause of our choosing you to be parliament-men was to deliver us from all kind of bondage and to preserve the commonwealth in peace and happiness. For effecting whereof we possessed you with the same power that was in ourselves to have done the same; for we might justly have done it ourselves without you if we had thought it convenient, choosing you (as persons whom we thought fitly qualified, and faithful) for avoiding some inconveniences.

_____

The distribution of dissident publications is always fascinating, and often terrifying considering the penalties faced: from protestant martyrologists under Queen Mary and Catholic apologists under Elizabeth, to samizdat distribution in the Soviet Union. The opening fifteen minutes of Sophie Scholl: the final days captures it all brilliantly and tragically.

0 -

New in Henry VII's time then?0

-

It's a good question. Henry both penned pamphlets and commissioned them (initially defending Papal supremacy, later promoting the reformation of the English church), but I don't know to what extent this was novel and to what extent already established practice. It is an interesting reminder, though, that pamphlets were a tool of the establishment, and not only of dissidents.

There were surely short, tract-like texts earlier, on religious and political subjects, likely emerging first from the universities and the network of humanist scholars, but I think you are right that printing gives birth to the pamphlet proper or, to put it another way, a pamphlet is in part defined by a significant number of cheaply produced copies.0

Categories

- All Categories

- 46 Introductions

- 3.9K Typeface Design

- 489 Type Design Critiques

- 568 Type Design Software

- 1.1K Type Design Technique & Theory

- 662 Type Business

- 868 Font Technology

- 29 Punchcutting

- 526 Typography

- 121 Type Education

- 326 Type History

- 79 Type Resources

- 112 Lettering and Calligraphy

- 33 Lettering Critiques

- 79 Lettering Technique & Theory

- 564 Announcements

- 95 Events

- 116 Job Postings

- 170 Type Releases

- 182 Miscellaneous News

- 278 About TypeDrawers

- 55 TypeDrawers Announcements

- 121 Suggestions and Bug Reports