Brain Sees Words As Pictures

Comments

-

Being so loose, it:

— Reduces bouma cohesion.

— Exhausts the visual field's horizontal range sooner, reducing the ratio of reading to saccades/line-returns.

— Requires more leading, hence more paging/scrolling.0 -

The human mind has grown to be enormously capable of combing data from all of its senses even with the cave man quickly distinguishing prey from predator in a busy horizon. We need not be shy of expanding the scope of research to include avenues not yet explored instead of assuming we have identified all of the players in the game.

Even regarding spacing, there is no universal solution. The typeface design encompasses spacing and indeed some examples require different spacing.

2 -

I'm confident that most folks grasp familiar words ideographically and unfamiliar words alphabetically.

3 -

@Nick Curtis Yes, and more generally common letter-clusters (which can be parts of words) that are sufficiently distinctive in notan (boumas). Also, with reading experience more boumas become familiar. This is why beginner/foveal reading favors all-caps and loose setting, while immersive reading suffers from those.

Larson's conclusions are limited to the fovea, for one simple reason: primitive field-testing. To be fair, E. B. Huey's words from 1908 still ring true: "And so to completely analyze what we do when we read would almost be the acme of a psychologist's achievement, for it would be to describe very many of the most intricate workings of the human mind, as well as to unravel the tangled story of the most remarkable specific performance that civilization has learned in all its history." Thankfully though the scientists in the paper(s) mentioned above have come significantly closer to the truth.0 -

Speaking as a designer, Spectral is spaced for too loosely for my taste, whether for online or print use.1

-

This paper shows that when you repeatedly show a person new words that the brain activation will change from the activation of a new word towards the activation of a known word, in regions of the brain associated with orthographic processing. It doesn’t say anything about seeing words as a picture. That is a misinterpretation of the Georgetown publicity office.

Johnathan Grainger wrote an excellent review of orthographic processing in Visible Language a couple years ago, “Orthographic Processing and Reading”. It’s fantastic.

http://visiblelanguage.herokuapp.com/issue/202/article/1392

6 -

That's one way to interpret it, but I find it blinkered (pardon the pun).

Letters are pictures. Groups of letters are pictures. There is no reason for the brain to refuse the efficiency of recognizing frequent and distinctive groups of letters as wholes deep into the field of vision where individual letters are undecipherable; also, there is plenty of evidence that the letterwise-inhibiting parafovea does play a large role in immersive reading. Flawed testing (self-fulfillingly limiting reading to the near-fovea) can give one false confidence against that natural conclusion.

Please find the funding to conduct properly immersive testing (crucially where the subjects don't realize they're being tested). You will have done the craft of type design a true service, versus the untenability of loosely-spaced capitals being the best for reading.0 -

Hrant H. Papazian said:versus the untenability of loosely-spaced capitals being the best for reading.But, but... of course "loosely-spaced capitals" are "the best for reading"! And I have the proof right here:

0

0 -

@John Savard PFRT!0

-

Certainly no practitioner's beliefs constitute empirical proof, but the below is some rare explicit encouragement that I hope makes it worth sharing here:

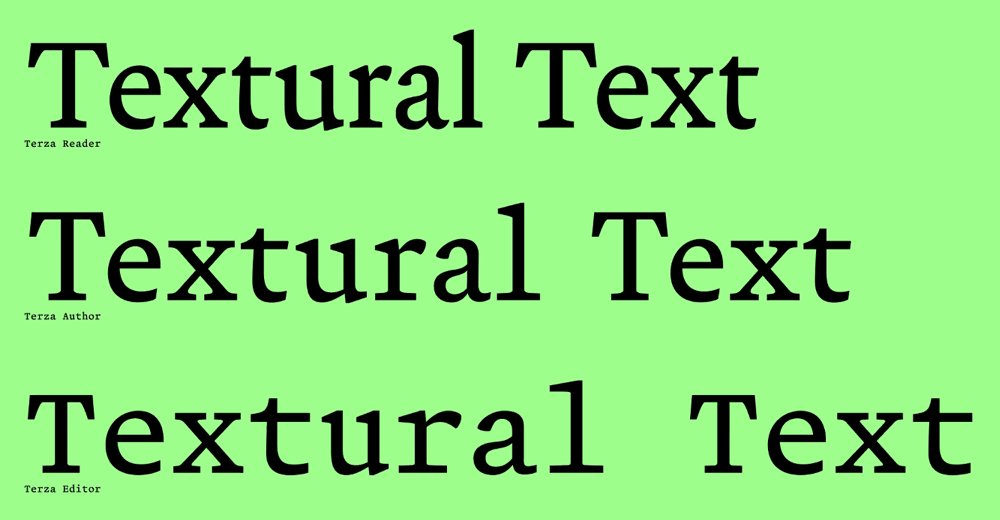

At the Typographics TypeLab event, Greg Gazdowicz of Commercial Type showed an interesting three-pronged typeface:

The difference between the Reader and Author cuts is that the former minds boumas, while the latter is about typing (which involves not immersive reading, but deliberative). Another slide:

(I'm not sold on the Editor cut, but that's moot here.)

BTW here's where you can catch the whole talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8Ce9d_2H5I&t=40705s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8Ce9d_2H5I&t=40705s

0 -

There is one issue with the talk: it is almost 12 hours in length.I do not see anywhere where it is mentioned at what point during the talk Greg Gazdowicz' presentation took place.Of course, though, YouTube lets one click on the progress bar: apparently Greg Gazdowicz appears at 11:18 in the video, near the end.He also mentions Terza in this video, which is only 15 minutes long:

0 -

@John Savard The whole video is day one of the conference; I actually cued up Greg's talk (using a feature of YouTube) but should have also mentioned the time stamp. Thanks for the link to the other video.0

-

We can measure the similarity with ASM (approximate string matching), which is not the same as human recognition, but there is some correlation.QuoinDesign said:While I can read Cmarbidge, Cgiarbmde doesn't work.

Cmarbidge has 3 of 9 letters in the wrong position:

Cgiarbmde has 6 of 9 letters wrong:

As humans we expect on the language level after deciphering

According to research at [some research location/organisation]

and

[name of a university] University,

Of course we need to know Cambridge. If not, we can use Google and get Cambridge as first hit.

Back to the topic of readability related to font design one example hard for OCR:

Recognised by OCR as 'eonnnnnicaio' and hard to match in a lexicon:

2 -

That's one of the best articles I ever read on visual recognition of text.Kevin Larson said:[...]

Johnathan Grainger wrote an excellent review of orthographic processing in Visible Language a couple years ago, “Orthographic Processing and Reading”. It’s fantastic.

http://visiblelanguage.herokuapp.com/issue/202/article/1392

1 -

Incidentally, while the resemblance is not as strong in Terza Reader as in the other two...Terza, understandably, resembles a number of currently fashionable typefaces, such as Alegreya. But it specifically has a resemblance to something else which I did not expect, which revealed to me that it may be the inspiration for many of today's fashionable typefaces.It is to the typewriter typestyle from IBM of Prestige Elite to which I refer. Incidentally, it was available for IBM's typebar typewriters before the Selectric came along. Because the early Selectrics didn't have a lighter impression for some characters, the period was redesigned to make it larger for the Selectric.So it seems that Prestige Elite, and not just an attempt to fuse Clarendon with Garamond, is behind many of today's popular serif typefaces.0

-

@Helmut Wollmersdorfer http://visiblelanguage.herokuapp.com/issue/202/article/1392

What was the typical WPM of the tests this was based one? A low WPM is usually the handiest clue that they weren't working with immersive reading. A more subtle one is the proportion of regressions: too low is bad news. (BTW, that page wouldn't load on Chrome – I had to use Edge.)0 -

[The page loads for me in Chrome Version 90.0.4430.212 on Mac OS]Hrant H. Papazian said:@Helmut Wollmersdorfer http://visiblelanguage.herokuapp.com/issue/202/article/1392

What was the typical WPM of the tests this was based one? A low WPM is usually the handiest clue that they weren't working with immersive reading. A more subtle one is the proportion of regressions: too low is bad news. (BTW, that page wouldn't load on Chrome – I had to use Edge.)

Most of the tests are the methods usual in cognitive psychology, i. e. seeing the brain as a black box. Medical science uses other tests (laser projection directly on the retina, EEG of brain regions, full control by a computer). The science is still not far away from the start.

IMHO there isn't one way we read text. We recognise low level features (edges, lines, angles, curves, circles, skeleton, area, colour, darkness), associated to a letter, symbol or something else (maybe a speckle, a wormhole or a book scorpion in the scan of an old book). Maybe we see the most frequent short words as a whole. In German the most frequent 207 words make 54 % of a text. It's reasonable that vision shortcuts the image of a whole word to its concept (a collection of sensual impressions related to a 'thing'). We also have trained language models (vocabulary, inflection, part of speech, phrases, orthography). Thus a fast reader needs not recognise each single letter or word and often doesn't recognise spelling errors.

But there is a difference between well trained and learning, adapting. Imagine someone reading 15th century English in a historic font. The speed slows down as not all characters are known, the orthography is different, so maybe phonetics help. But if you don't know one letter, e. g. the \H of Schwabacher and the word is unknown and ambiguous, you maybe need to read a few pages first to learn the \H.

It took me 3 times to understand the following text word by word and still can't read it fast:

Could you recognise the year in Roman numerals within one second?1 -

Testing methods are one thing, making sure the test subjects are experienced and reading naturally is another... Too often they're college students hooked up to immersion-killing equipment. This precludes meaningful results. Worse still, it motivates poor design through a veneer of legitimacy.

Agreed that there isn't one way we read text. I believe there are two principal ones: deliberative and immersive. The former requires only a trivially-ensured level of legibility; the latter is far murkier – where true readability comes out to play.

Bingo. And I believe not just whole words, but clusters of letters that are sufficiently frequent and distinct (particularly relevant for German with its wealth of word compounding) which I call "boumas". This is what the letterwise-compilation model ignores, duping designers into a cavalier (artsy) attitude towards reading functionality, most obvious of late in loose spacing.It's reasonable that vision shortcuts the image of a whole word

As for familiarity, of course that's a big factor. But intrinsic attributes of readability (and legibility) are also at play, and cannot be ignored by any serious text face designer.1 -

Hard to make out any of that text, it seems to be some kind of rude and simple form of English.

1 -

It’s late middle English or early modern English, apparently from 1481.

By the time I reached the end of the block I was reading it pretty quickly—but still less than half the speed of regular TypeDrawers posts.2 -

But, but... of course "loosely-spaced capitals" are "the best for reading"! And I have the proof right here:I can't speak for your experience but, in mine, I'm asked to name the individual letters, not to read them as words.

0 -

Hrant H. Papazian said:For example when something like Spectral gets released, you have to be able to grasp what's wrong with it ITO spacing.I took a look at this page:which I had to search for, as the link on the page you linked to is now broken...and the first thing I saw was that Spectral was intended as a typeface for computer screens rather than print on paper. This already led me to dismiss your criticism of its spacing, since legibility on a computer screen is apparently a reasonable excuse for a bit of letterspacing. Despite the fact that the typeface used for this forum doesn't seem to need that.And on that page, further down, is a comparison between Spectral and a print sample from an old edition of Gargantua by Descartes. (In fact, though, it's from the better-known work, also titled Gargantua, by Rabelais.) The spacing of Spectral only seemed very slightly wider.And yet, from your phrasing, I would have expected Spectral to be an egregious example of bad spacing. That does not seem to be the case from the initial information I have found.EDIT: However, basing my judgment of the typeface on a page that is intended to promote it is hardly fair. So, since it's from Google Fonts and thus free, I downloaded and installed it to give it a closer look.I decided I'd start with Spectral Medium instead of regular Spectral, since it was slightly bolder, and so it would probably be less affected by any excess spacing flaw it might have.

It's a good thing I did. While I might not have noticed any excess space in regular Spectral, it was clear and obvious that Spectral Medium was indeed too widely spaced, just as Hrant was claiming.I chose 18 points, in hopes it was large enough to avoid artifacts due to the finite size of the pixel. But maybe that wasn't enough. So I gave it another chance.

It's a good thing I did. While I might not have noticed any excess space in regular Spectral, it was clear and obvious that Spectral Medium was indeed too widely spaced, just as Hrant was claiming.I chose 18 points, in hopes it was large enough to avoid artifacts due to the finite size of the pixel. But maybe that wasn't enough. So I gave it another chance. That some letters look bolder than others is an artifact of the fact that I had reduced the image, but the spacing between letters is not.I'm definitely inclined to agree that Spectral Medium, at least, does have a bit too much space between the letters.1

That some letters look bolder than others is an artifact of the fact that I had reduced the image, but the spacing between letters is not.I'm definitely inclined to agree that Spectral Medium, at least, does have a bit too much space between the letters.1 -

What is a "picture" when the brain sees it? Or... What is it about a thing we see that makes it a picture?

Isn't this about patterns and pattern recognition? Yes, recognising patterns is an important assist to any repeated task involving perception, and as a rule we're pretty good at it. After learning what raspberries look and taste like, we see them as delicious treats instead of lumpy red things we're not so sure about. Is there a reason reading would be any different?2

Categories

- All Categories

- 46 Introductions

- 3.9K Typeface Design

- 490 Type Design Critiques

- 569 Type Design Software

- 1.1K Type Design Technique & Theory

- 663 Type Business

- 868 Font Technology

- 29 Punchcutting

- 529 Typography

- 123 Type Education

- 326 Type History

- 80 Type Resources

- 112 Lettering and Calligraphy

- 33 Lettering Critiques

- 79 Lettering Technique & Theory

- 563 Announcements

- 94 Events

- 116 Job Postings

- 170 Type Releases

- 182 Miscellaneous News

- 278 About TypeDrawers

- 55 TypeDrawers Announcements

- 121 Suggestions and Bug Reports