first use of arrows to indicate directions...

Russell McGorman

Posts: 275

... On signage and in sign-writing specifically, but in typography, lettering and even technical drawings, maps and so on *, when did the arrow become a symbol for directions and ultimately, THE the universal symbol to say "go that-a-way" ? I have seen references to using a foot print shape carved in paving stones (as in "follow the foot prints to get to the brothel") and of course manicules have been used in typesetting since the 1500's, but when did arrows become symbols to show directions.

*as I type I keep thinking of more places they're used.

*as I type I keep thinking of more places they're used.

Tagged:

3

Comments

-

My bet would be long before written language, people scratched arrows in the dirt ;-)2

-

I've heard of several primitive symbols for that. The foot print, mentioned above, which I think was in ancient Greece or Rome and Joe Clark once mentioned bird foot prints used in South America, which is fun thought because that's basically a backwards arrow. (Joe?) but what I am trying to track down is when did it become common place as a symbol?

Why I am asking? I've worked many with wayfinding signage and it was that work that got me into designing type, so I aways include directional arrows in my fonts. It's just a quirk, because so far, there is no practical purpose in doing so. Right now, I am currently working on a blackletter one and I want some arrow references that fit the style.1 -

What about medieval weaponry? There must be arrowheads from the time period of Blackletter?0

-

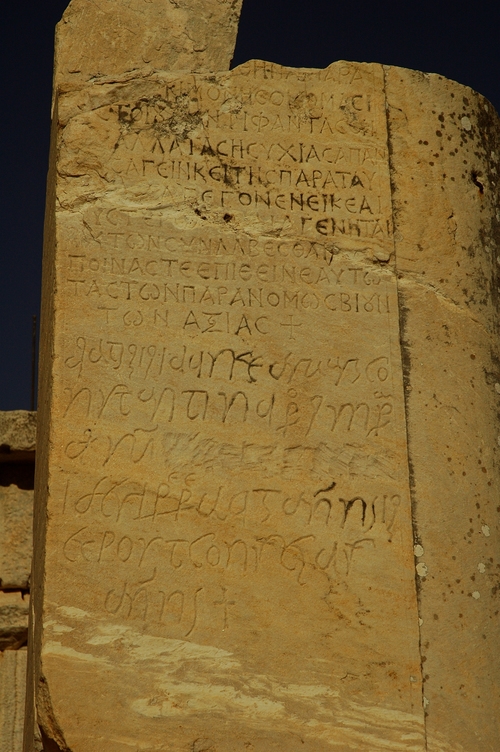

The "this way to the brothel" footprint is in the pavement in Ephesus, on the road between the temple of Diana and the forum.

It's a fun place for typographers to visit.

5 -

Article here seems to indicat that they first appear in the 18th C.

https://printinghistory.org/arrow/

1 -

I can imagine Robin and his merry men may have utilized them as graphic elements on the forest floor of Sherwood.

2 -

"This Way to the Boars Head Inn" ;-)1

-

@ Si Daniels; Or coming through the Sherif's window with a note attached.

1 -

Highgate Cemetery.

4

4 -

Columbarium is the most interesting word I’ve learned all month!2

-

Good thing Nick put a finger on the word for you, James ;-)1

-

1

-

Thanks.

So, here's where I left it a couple of days ago. I've since been looking at some illuminations showing archers and heraldic sources, thinking of the British Army's Board of Ordinance broad arrow symbol: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broad_arrow

0 -

Joe Clark once mentioned bird foot prints used in South America, which is fun thought because that's basically a backwards arrow

I was parroting the squawk from late lamented design peacock Paul Arthur, who crowed that anyone from a rural upbringing would view a standard arrow with 45° lines as pointing the wrong way because chicken footprints point behind them.1 -

Oh... Where'd I get south America from? Oh well. Thanks for reminding me0

-

I wrote something on the subject:

1) Leonard Digges and Galileo Galilei arrows

https://synsemia.org/2011/01/04/arrow-as-a-synsemic-perspective/

2) Pointers (aztec fists, phylacterion...)

https://synsemia.org/2011/01/05/alternatives-to-the-arrow-and-alternative-functions-of-the-arrow/

3) Some "maniculae" (fists)

https://synsemia.org/2010/12/17/633/

4) Daniele Capo on arrows and vectors

https://synsemia.org/2011/05/18/frecce-e-vettori-1/

5) Giovanni Anceschi found an arrow attributed at Sacromonte di Varallo that might have been painted in the first half of XVI century (picture by Riccardo De Franceschi).

6 -

Thank you.0

-

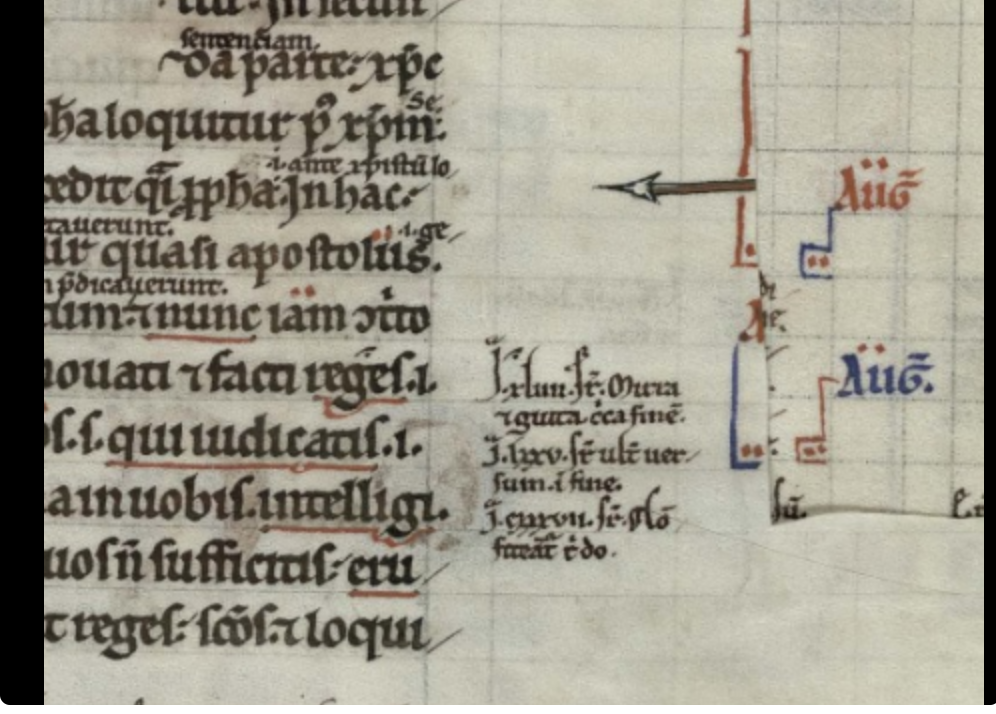

Some days ago a friend of mine came across this:

http://trin-sites-pub.trin.cam.ac.uk/james/viewpage.php?index=453

a glossed psalter from XII century. We are studying the manuscript, but the sign seems to be used to indicate.

In the same manuscript see also folio 33 recto and folio 35 recto.1 -

-

The harpoon is always embraced by somebody, where it appears alone, the page is cut.0

-

What a fascinating discussion.

I wonder about precise usage: The early example that Luciano Perondi’s article cites, from 1596, uses arrows as pointers to point to exact spots in an illustration. I’m not sure about the uses above (with the harpoon), do these point to specific lines in the main text?

This got me wondering, what is the relation between the use of the (typographical) arrow from first pointing to a precise location — which would be congruent with the idea of an arrow in the sense of a weapon hitting a target — to indicating a rough, general direction (as seen nowadays on traffic signs etc, and the possibly 16th century painted one above), which is further removed from that literal idea and seems potentially like more of a stretch to make from a physical arrow? I wonder if the former came first & then gradually evolved into the latter.

1 -

I think that the pointing arrow predates written language--even if it was just a way to keep from getting lost.0

-

No answers from me, just another question: What about early examples of arrow-like points on a compass, or hands on a clock? It seems like these would have reinforced an iconographic meaning.

2 -

Thanks! I remember a compass rose showing the 12 winds by Matthew Paris, 13th century. North is on the left East on the top, the triangles seems to point directions, but just 4 of the 12 directions.

1

1 -

About the image I sent yesterday, it is an attempt of harmonization between the 12 wind system and 16 wind system (sorry, I was a bit in hurry, going to take a train):

The Book of Additions (Liber Additamentorum), British Library, Cotton MS Nero D I, fol. 185v

http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/illmanus/cottmanucoll/t/011cotnerd00001u00185v00.html

The "De Ventis" of Matthew Paris, E. G. R. Taylor, in Imago Mundi, Vol. 2 (1937), pp. 23-26

http://www.jstor.org/stable/1149830?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Matthew Paris, R Vaughan, Cambridge University Press, 1979

https://books.google.it/books?id=xec7AAAAIAAJ

0 -

About the Harpoon, I'm working with a friend to a translation of the smaller glosses (the others are well known classical glosses, probably also the others are well known, but we are rather ignorant on the subject), in order to be sure that the harpoon is pointing or highlight something. Until now it seems so. When there is a small glossa, there is a Church father with the harpoon pointing the text and the explanation of what he wrote and a phylakterion "summarizing". But I prefer to wait when I have a more complete translation before saying something.Nina Stössinger said:What a fascinating discussion.

I wonder about precise usage: The early example that Luciano Perondi’s article cites, from 1596, uses arrows as pointers to point to exact spots in an illustration. I’m not sure about the uses above (with the harpoon), do these point to specific lines in the main text?

This got me wondering, what is the relation between the use of the (typographical) arrow from first pointing to a precise location — which would be congruent with the idea of an arrow in the sense of a weapon hitting a target — to indicating a rough, general direction (as seen nowadays on traffic signs etc, and the possibly 16th century painted one above), which is further removed from that literal idea and seems potentially like more of a stretch to make from a physical arrow? I wonder if the former came first & then gradually evolved into the latter.

1

Categories

- All Categories

- 46 Introductions

- 3.9K Typeface Design

- 490 Type Design Critiques

- 569 Type Design Software

- 1.1K Type Design Technique & Theory

- 663 Type Business

- 868 Font Technology

- 29 Punchcutting

- 527 Typography

- 122 Type Education

- 326 Type History

- 79 Type Resources

- 112 Lettering and Calligraphy

- 33 Lettering Critiques

- 79 Lettering Technique & Theory

- 563 Announcements

- 94 Events

- 116 Job Postings

- 170 Type Releases

- 182 Miscellaneous News

- 278 About TypeDrawers

- 55 TypeDrawers Announcements

- 121 Suggestions and Bug Reports