During every minute of every day of 2014, according to Andrew Keen’s new book, the world’s internet users – all three billion of them – sent 204m emails, uploaded 72 hours of YouTube video, undertook 4m Google searches, shared 2.46m pieces of Facebook content, published 277,000 tweets, posted 216,000 new photos on Instagram and spent $83,000 on Amazon.

By any measure, for a network that has existed recognisably for barely 20 years (the first graphical web browser, Mosaic, was released in 1993), those are astonishing numbers: the internet, plainly, has transformed all our lives, making so much of what we do every day – communicating, shopping, finding, watching, booking – unimaginably easier than it was. A Pew survey in the United States found last year that 90% of Americans believed the internet had been good for them.

So it takes a brave man to argue that there is another side to the internet; that stratospheric numbers and undreamed-of personal convenience are not the whole story. Keen (who was once so sure the internet was the answer that he sank all he had into a startup) is now a thoughtful and erudite contrarian who believes the internet is actually doing untold damage. The net, he argues, was meant to be “power to the people, a platform for equality”: an open, decentralised, democratising technology that liberates as it empowers as it informs.

Instead, it has handed extraordinary power and wealth to a tiny handful of people, while simultaneously, for the rest of us, compounding and often aggravating existing inequalities – cultural, social and economic – whenever and wherever it has found them. Individually, it may work wonders for us. Collectively, it’s doing us no good at all. “It was supposed to be win-win,” Keen declares. “The network’s users were supposed to be its beneficiaries. But in a lot of ways, we are its victims.”

This is not, Keen acknowledges, a very popular view, especially in Silicon Valley, where he has spent the best part of the past 30-odd years after an uneventful north London childhood (the family was in the rag trade). But The Internet is Not the Answer – Keen’s third book (the first questioned the value of user-generated content, the second the point of social media; you get where he’s coming from) – has been “remarkably well received”, he says. “I’m not alone in making these points. Moderate opinion is starting to see that this is a problem.”

What seems most unarguable is that, whatever else it has done, the internet – after its early years as a network for academics and researchers from which vulgar commercial activity was, in effect, outlawed – has been largely about the money. The US government’s decision, in 1991, to throw the nascent network open to private enterprise amounted, as one leading (and now eye-wateringly wealthy) Californian venture capitalist has put it, to “the largest creation of legal wealth in the history of the planet”.

The numbers Keen reels off are eye-popping: Google, which now handles 3.5bn searches daily and controls more than 90% of the market in some countries, including Britain, was valued at $400bn last year – more than seven times General Motors, which employs nearly four times more people. Its two founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, are worth $30bn apiece. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, head of the world’s second biggest internet site – used by 19% of people in the world, half of whom access it six days a week or more – is sitting on a similar personal pile, while at $190bn in July last year, his company was worth more than Coca-Cola, Disney and AT&T.

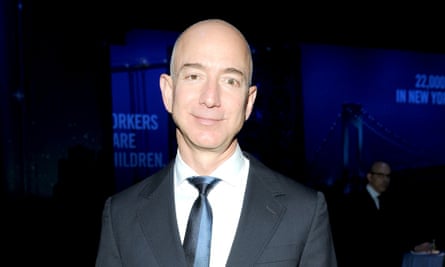

Jeff Bezos of Amazon also has $30bn in his bank account. And even more recent online ventures look to be headed the same way: Uber, a five-year-old startup employing about 1,000 people and once succinctly described as “software that eats taxis”, was valued last year at more than $18bn – roughly the same as Hertz and Avis combined. The 700-staff lodging rental site Airbnb was valued at $10bn in February last year, not far off half as much as the Hilton group, which owns nearly 4,000 hotels and employs 150,000 people. The messaging app WhatsApp, bought by Facebook for $19bn, employs just 55, while the payroll of Snapchat – which turned down an offer of $3bn – numbers barely 20.

Part of the problem here, argues Keen, is that the digital economy is, by its nature, winner-takes-all. “There’s no inevitable or conspiratorial logic here; no one really knew it would happen,” he says. “There are just certain structural qualities that mean the internet lends itself to monopolies. The internet is a perfect global platform for free-market capitalism – a pure, frictionless, borderless economy … It’s a libertarian’s wet dream. Digital Milton Friedman.” Nor are those monopolies confined to just one business. Keen cites San Francisco-based writer Rebecca Solnit’s incisive take on Google: imagine it is 100 years ago, and the post office, the phone company, the public libraries, the printing houses, Ordnance Survey maps and the cinemas were all controlled by the same secretive and unaccountable organisation. Plus, he adds, almost as an afterthought: “Google doesn’t just own the post office – it has the right to open everyone’s letters.”

This, Keen argues, is the net economy’s natural tendency: “Google is the search and information monopoly and the largest advertising company in history. It is incredibly strong, joining up the dots across more and more industries. Uber’s about being the transport monopoly; Airbnb the hospitality monopoly; TaskRabbit the labour monopoly. These are all, ultimately, monopoly plays – that’s the logic. And that should worry people.”

It is already having consequences, Keen says, in the real world. Take – surely the most glaring example – Amazon. Keen’s book cites a 2013 survey by the US Institute for Local Self-Reliance, which found that while it takes, on average, a regular bricks-and-mortar store 47 employees to generate $10m in turnover, Bezos’s many-tentacled, all-consuming and completely ruthless “Everything Store” achieves the same with 14. Amazon, that report concluded, probably destroyed 27,000 US jobs in 2012.

“And we love it,” Keen says. “We all use Amazon. We strike this Faustian deal. It’s ultra-convenient, fantastic service, great interface, absurdly cheap prices. But what’s the cost? Truly appalling working conditions; we know this. Deep hostility to unions. A massive impact on independent retail; in books, savage bullying of publishers. This is back to the early years of the 19th century. But we’re seduced into thinking it’s good; Amazon has told us what we want to hear. Bezos says, ‘This is about you, the consumer.’ The problem is, we’re not just consumers. We’re citizens, too.”

One chapter of the book is devoted to Keen’s lament for Rochester, the home town of Eastman Kodak – a company that in 1989, the year Tim Berners-Lee invented the web, was worth $31bn and employed 145,000 people. It filed for bankruptcy in 2012. Just the previous year, as a timeline at its headquarters records, 380bn photographs were taken around the world – 11% of all the photographs ever taken – and the number of images hosted by Facebook (a business whose model is the monetisation of friendship and whose product is, essentially, us and our lives) was approaching 500bn. Meanwhile, 55,000 Kodak pensioners are out of luck.

Silicon Valley talks about the digital economy creatively “disrupting” what went before; Keen thinks a better word might be “destruction”. He insists he is “not a Luddite. I have no objection to the destruction of the old – providing there’s something to take its place. This isn’t a technological issue; it’s a question about the world we want to live in. Look, I’ve sat in the back of enough dirty cabs and been insulted by enough drivers to know the taxi business is very far from perfect. It needs to modernise, become more accountable.

“But Uber? It’s a platform. They say everyone can become a driver, but are these jobs? My problem with Uber is not that it’s new, not even that it’s sweeping away a whole old system – it’s that it’s replacing it with … nothing. This is the gig economy. The so-called ‘sharing’ economy is actually dominated by a few companies, worth tens of billions of dollars. Do we really want to live as a precariat, perpetually selling ourselves on one network or other? Take it further: can the internet really replace healthcare, education, government? Can teachers and lawyers and doctors be replaced by a tiny group of online superstars? Some people think they can. They think the internet is the answer. I think the internet is more like the question for our 21st-century future.”

Keen confesses to being “perhaps a bit of a content snob, although only in the sense that I value skilled labour and appreciate good content”. He is, he says, particularly concerned by the impact of the internet’s “culture of free” on the creative and media industries. “If there’s no exchange of cash for your article, your photograph, your movie, your book, your song, how else are you supposed to make money?” he asks. “It’s not an original point, sure. But it’s been almost 50 years since the first computer-to-computer communication now; 25 years since the birth of the web. We’ve constantly been told: wait, don’t worry, it’s a young medium, something will emerge … But nothing has. For creatives, this has been a disaster.”

The number of photographers’ jobs in the US has fallen by 43%, he notes; the number of newspaper editorial jobs by 27%. He cites US singer-songwriter Ellen Shipley, who calculated in 2012 that one of her most popular tracks was streamed 3.1m times on the internet radio Pandora, for which she received a total of $31.93, and points to the 45% of revenue skimmed off all independently produced content on YouTube. Meanwhile, the internet’s inherent “1% model” is functioning perfectly: in 2013, Keen notes, the top 1% of music artists received 77% of all artist-recorded music income. Blockbusters do brilliantly; most of the rest withers.

“These new monopolistic platforms are more powerful, more wealthy and fundamentally indifferent to creativity,” he argues. “So I think when we look back, we might see that what we have now is actually lot worse than what we started with. Maybe, even, big media is not as evil as everyone makes out. Publishing houses, record labels, the Guardian – how much money have you guys lost over the past few years? – were and are made up of people who care about quality content, and they’re being swept away. We’re destroying the old, and what are we replacing it with? Anonymous people on Reddit spreading rumours, angry people on Twitter, celebrities online with millions of followers, selling their brand?”

Rather than encouraging creativity, stimulating competition, creating jobs, distributing wealth and promoting equality, Keen argues, the internet is in fact doing the reverse. Socially and culturally, it’s the same: “Rather than creating more democracy,” he writes in the introduction to The Internet is Not the Answer, “it’s empowering the rule of the mob. Rather than encouraging tolerance, it’s unleashed such a distasteful war on women that many no longer feel welcome on the network … Rather than making us happy, it’s compounding our rage.”

Not, he says again, that he would ever try to argue that the web has not helped us to communicate: “Even I wouldn’t dare do that. There’s obviously a huge amount of very real communication on the web.” But he does have his issues with social media.

If the “winnowing away” of 19th- and 20th-century industrial society is producing an “ever more atomised, more fragmented, more individualised” world in which “we are all basically our own brands – having to invent and reinvent ourselves because the old associations, the old certainties, the old identities are vanishing”, then, Keen argues, the internet is the perfect platform for us to do that. “That’s what we do, distribute our brands,” Keen says. “With the twist, of course, that in this particular economy, we’re also the product. The illusion of social media is that we want to be social; the reality is we’re selling ourselves. Or, at least, we think we are: actually, it’s selling us. We’re all working for Facebook and Google.”

What about social media’s role in organising protest and as a catalyst for change – in, for example, the Occupy movement, or the Arab Spring? Even there, Keen has his doubts. “It may have helped undermine old autocracies, but now it’s descending into chaos and warring tribes just like on the ground. We’ve thrown out the information gatekeepers and what we’ve got is propaganda.” During the July 2014 Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he points out, Israel was employing 400 students to run Facebook pages in five languages, while Hamas’s military wing, al-Qassam, was busily tweeting its line to thousands of followers.

Not much on social media is truly social, he argues. “We personalise,” he says. “So, you know, it’s kind of social, but in a very personalised way … One of the most troubling things for me about social media is the lack of diversity. It’s like going to some expensive US college. You only meet people like yourself.” Then there’s the whole privacy issue: “The internet is becoming structurally parochial, like a village. So not only does everyone from the NSA to the big internet companies know pretty much everything there is to know about us, but we’re all clustering in these tighter and tighter little ideological and cultural networks. There’s no serendipity, no stumbling upon random people or random ideas. Everything is pre-ordained; you’re served with what they know will suit you.”

Plus, of course, the internet is increasingly full of angry people. “It’s not that the net made us angry,” says Keen, “but it has become the funnel for our anger. We’re all now in the business of blaming someone else, we’re all obsessed with the meaningless indiscretions of strangers, and we have a platform for it. The internet’s a really great tool for persecuting people we don’t know, who we’re utterly indifferent to, about stuff that is essentially irrelevant. Stuff that, in a pub, we’d forget about in 30 seconds.”

Look, he says, at Justine Sacco, the PR executive famously shamed – and fired – after tweeting: “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get Aids. Just kidding. I’m white!” In a pub, says Keen, “We’d say, ‘That’s a stupid thing to say,’ and move on. We wouldn’t throw her out, complain to her employers, get her fired, put her in the stocks to be publicly pelted …”

So if the internet is actually the question, what’s the answer? A different internet altogether, Keen believes. Socially, he thinks, we’re all going to have to become “a whole lot more tolerant. Get over this fury at strangers.” But mainly, he thinks the time has come for “the regulators and the entrepreneurs to understand that they have to work together. That this conversation really has to happen; that we have to realise the internet has not been an unmitigated success.”

Because there is, he believes, something “quite disturbing, really quite problematic, going on at the root of our culture about this networked world that we’re slipping and sliding our way into. About how we engage with other people; how we think about society, politics, values. There has been a profound, structural change in the way we all do business: personally, socially, culturally and certainly economically. A very major shift in how we organise society. And we all need to wake up to that.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion