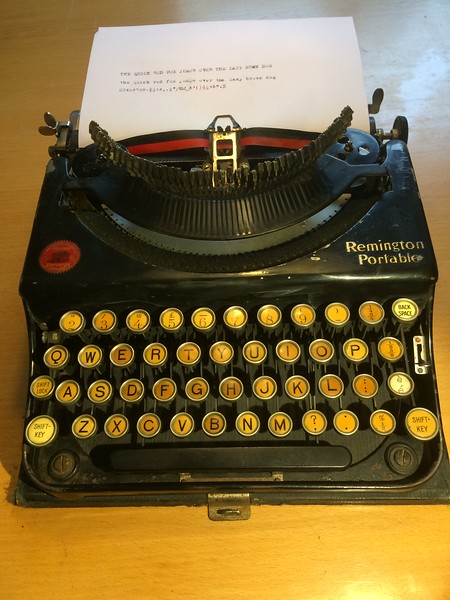

TYPEWRITER: Replacing The Drawcord On A Remington Portable.

Posted: January 30, 2019 Filed under: Typewriters | Tags: drawstring, how-to, portable, Remington, repair, Replacing 11 CommentsThe machine used in this article is a 1924 Remington Portable #1, but the drawcord mechanics are the same on the Portable #2 and #3, so, let’s start:

I’ve replaced several drawcords on different Remington Portables. Below is my method (not the method) for replacing the broken cord with a new cord. What you need is:

- a magnetic rod to ‘lock’ the main spring, I use a flashlight with a magnetic bottom,

- a cord to serve as a drawcord. I use thin black woven cord intended for venetian blinds,

- a piece of wire to finagle the cord through the holes in the main spring. I use a dental hook for that,

- a sharp screwdriver,

- a thin wooden/bamboo stick, I use a ‘saté stick’ for skewering meat, but as long as it’s thin and about 20cm long (like a thin crocheting hook/needle), it will do,

- A soft cushion to put the machine on, I use a piece of foam.

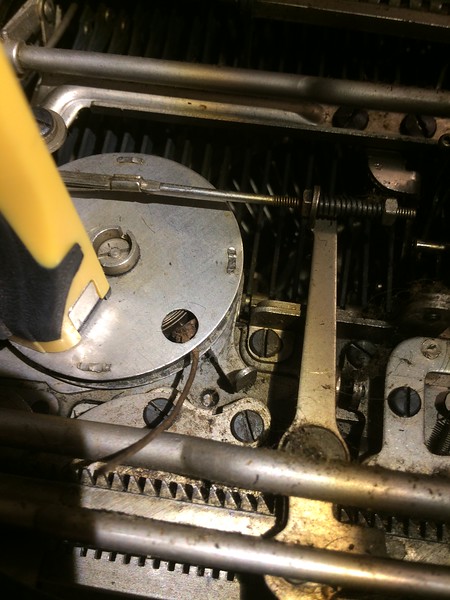

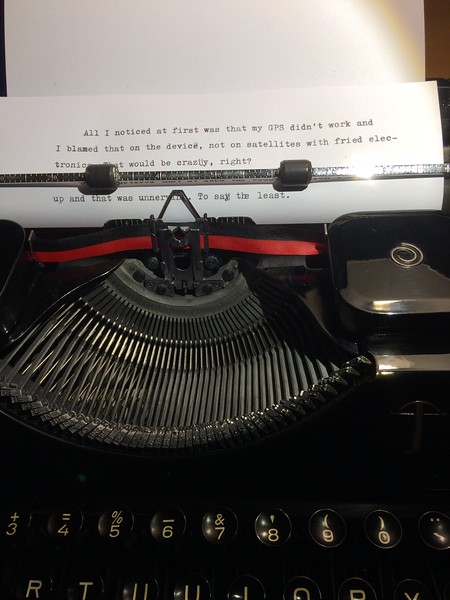

First, put the Remington Portable upside down on the cushion with the carriage close to you. Holding the magnetic rod handy, you start winding up the spring in the main spring housing so it nestles tightly against the axle and the small round hole is exposed, then place the magnetic rod on the mainspring housing so it stays in position.

Use the dental hook to fish the cord from the hole.

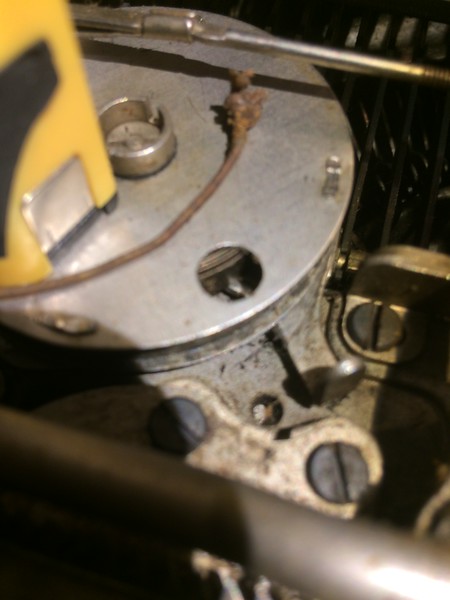

When you have removed the piece of cord, put a new piece of cord through the side into the main housing and pull it up through the hole.

Tie a tight knot in the short part that comes out of the hole and pull the cord to push that knot into the hole next to the coiled spring.

Remove the magnetic lock and slowly let the spring in the main housing uncoil and press up against the knot. When the spring uncoils, keep the cord up so it won’t catch under the mainspring housing. When the spring is totally uncoiled, you wind up the housing 4 rotations. This is more than enough to pull the carriage. Lock the mainspring housing with the magnetic rod again. The hole with the cord coming out is at your side, the side of the carriage.

Pull the carriage all the way to your right (fully extended carriage), and lead the cord around the tiny pulley and hook the cord under the guide hook.

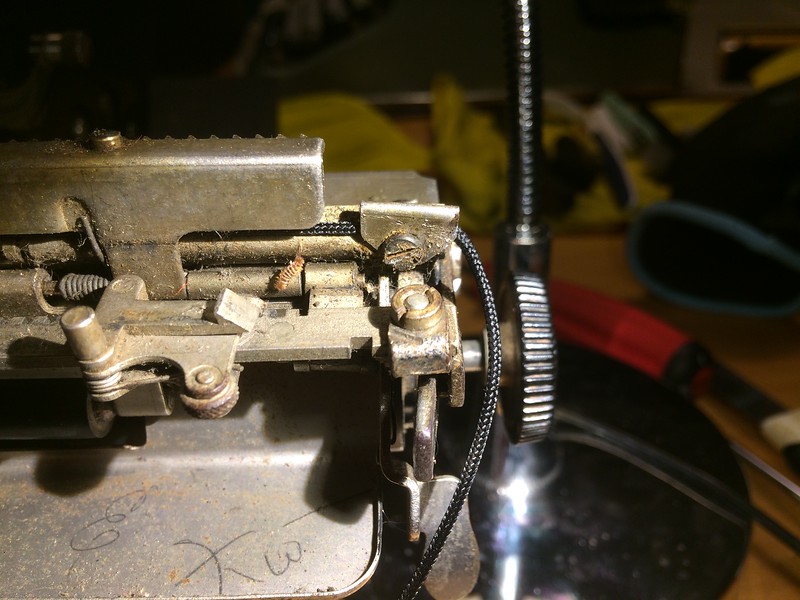

Tape the end of the cord to a stick to thread the cord underneath the carriage. Make sure the cord travels straight under the carriage (over the carriage now that the machine is upended, of course) to the far end.

The drawcord is pulled taut and clamped between the carriage and that little brass hook, screwed down tightly. Originally, the cord is clamped inside that little brass thingy, but that folded brass part is difficult to unfold and might break. So I hold the cord against the carriage over the screw, push the brass hook into position behind the screw and tight the screw.

When you are sure the cord is tightly clamped, add a knot to the end for security.

And your Remington Portable is ready for use again!

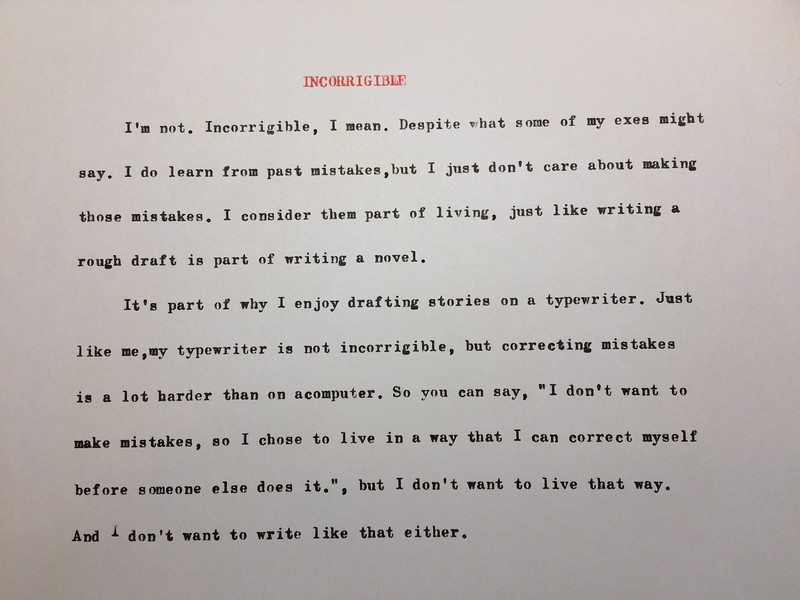

Typecast essay: Incorrigible.

Posted: December 24, 2018 Filed under: opinion, Typecast, Typewriters, Writing, writing skills | Tags: draft, essay, life, novels, scars, Typecast, typewriter, Vespa, writer life 2 Comments

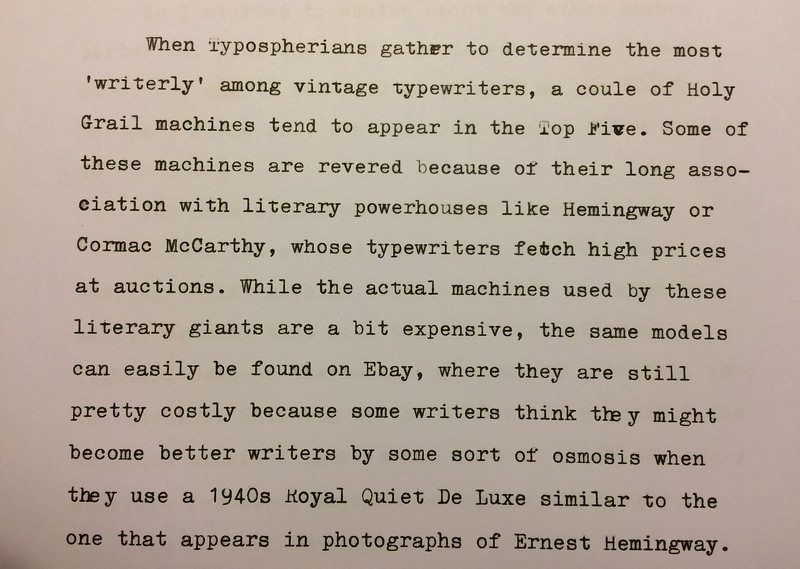

Typecast: Hello Gorgeous!

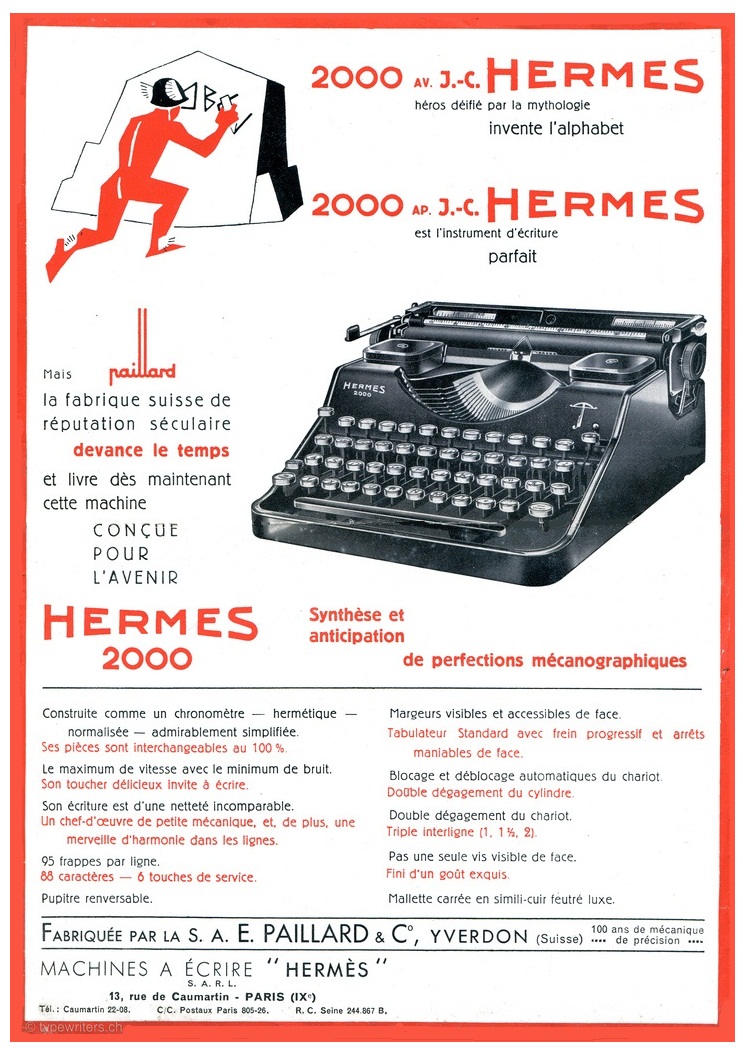

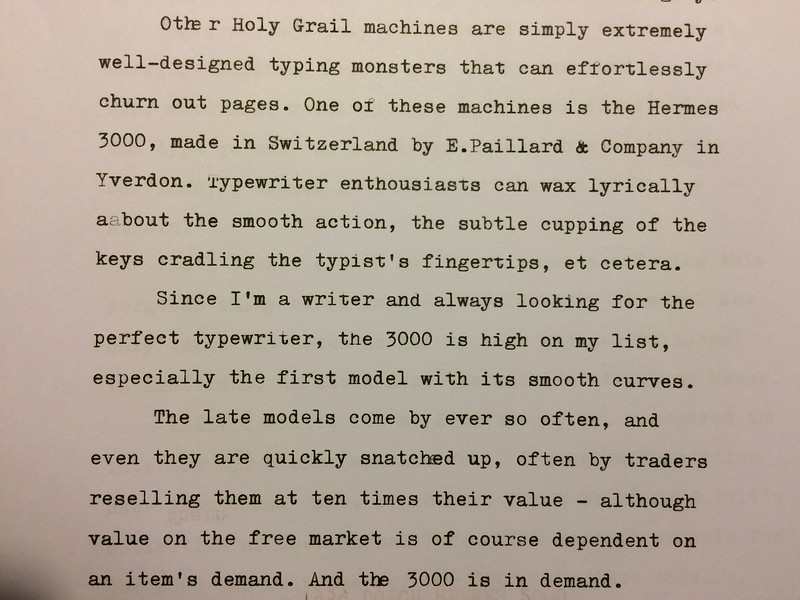

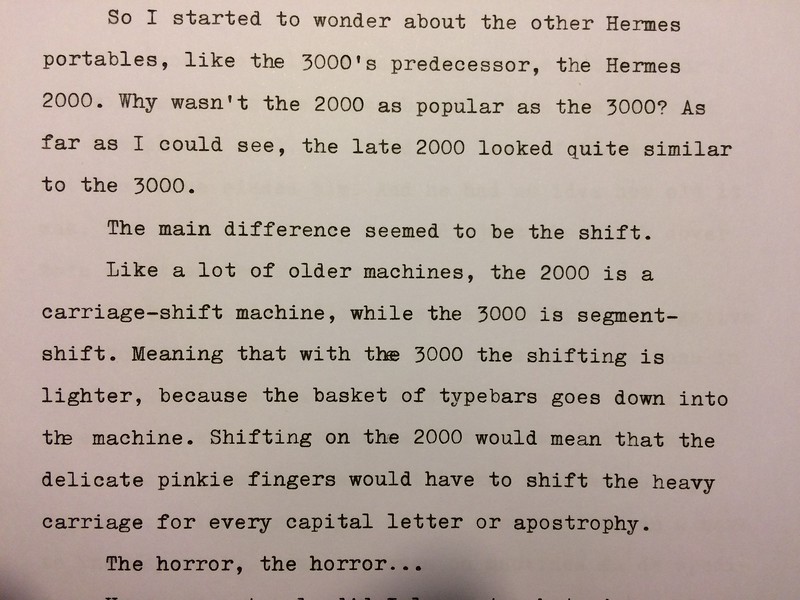

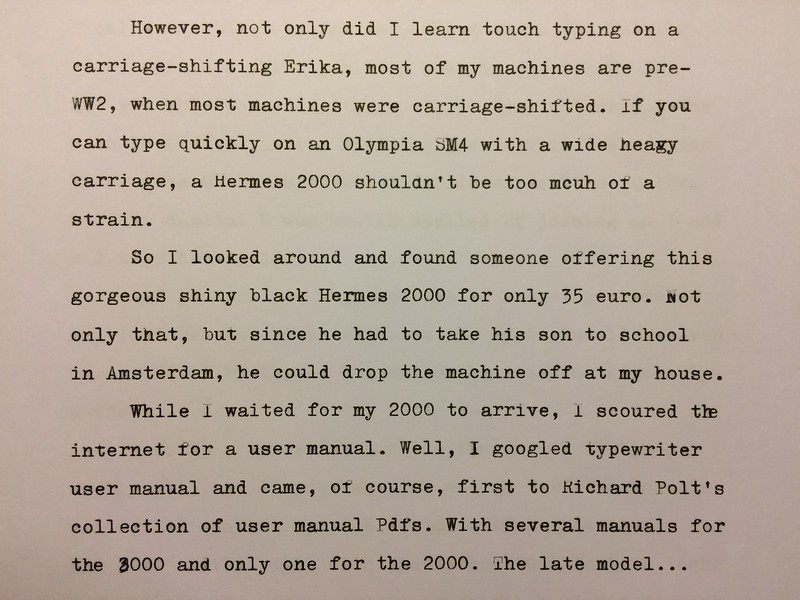

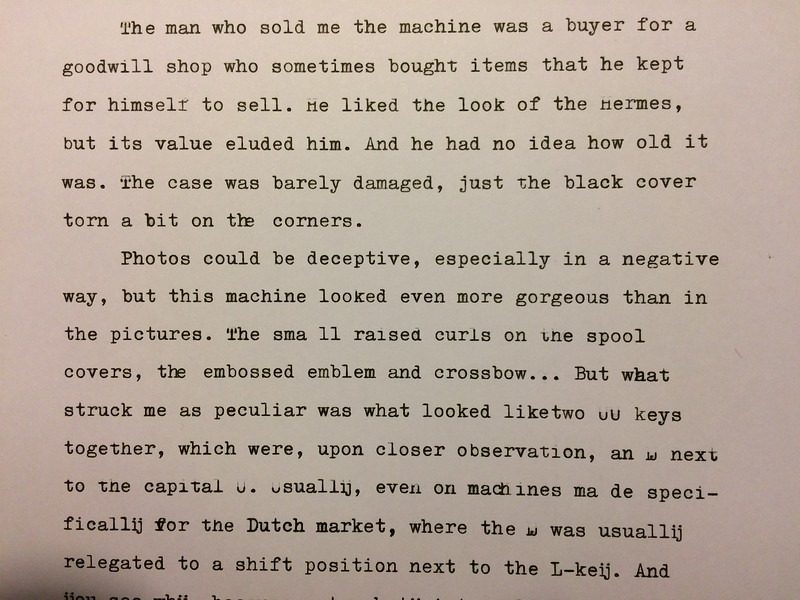

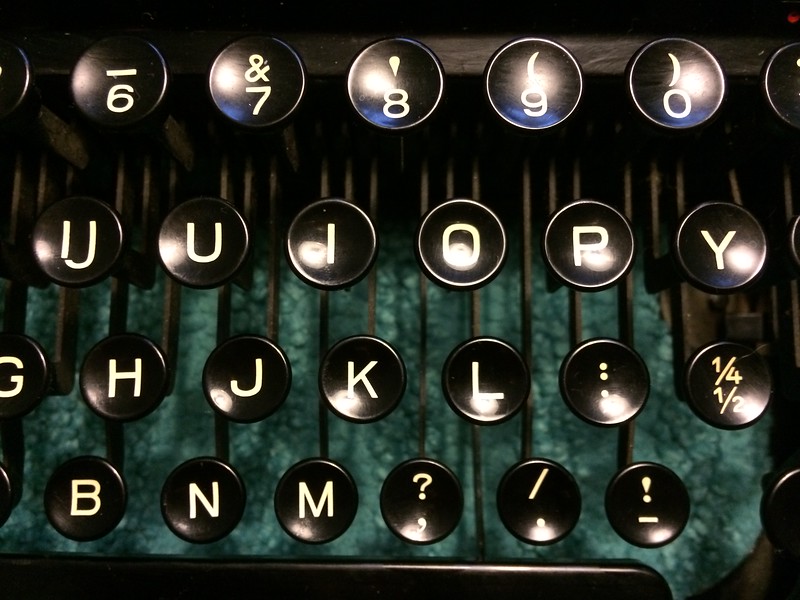

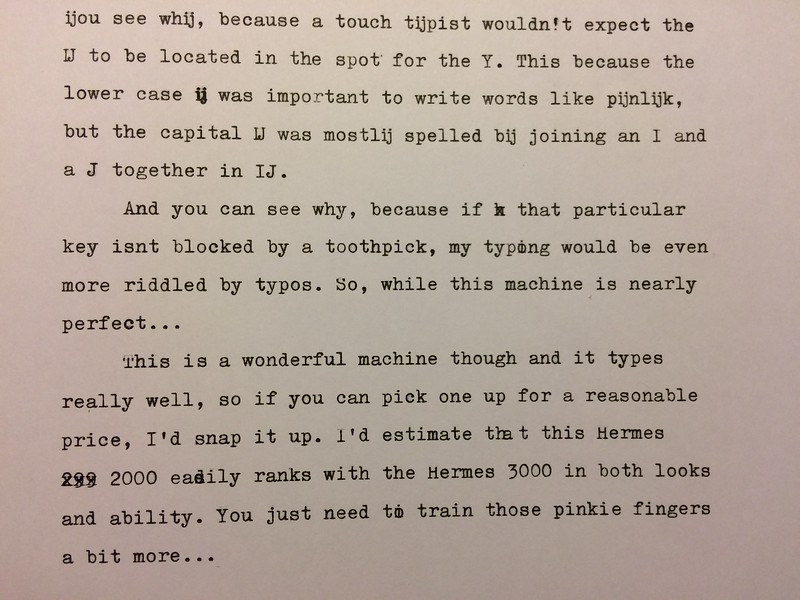

Posted: December 18, 2018 Filed under: Typecast, Typewriters, Writing | Tags: Cormac McCarthy, Corona, Hemingway, Hermes 2000, Hermes 3000, manual, manual typewriter, Richard Polt, Royal Quiet De Luxe, Typecast, typewriter, User Manuals 5 Comments

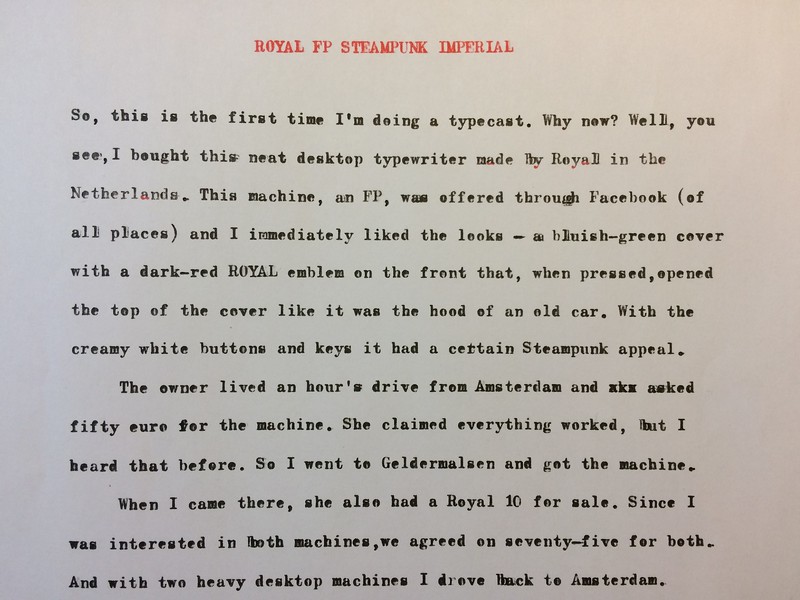

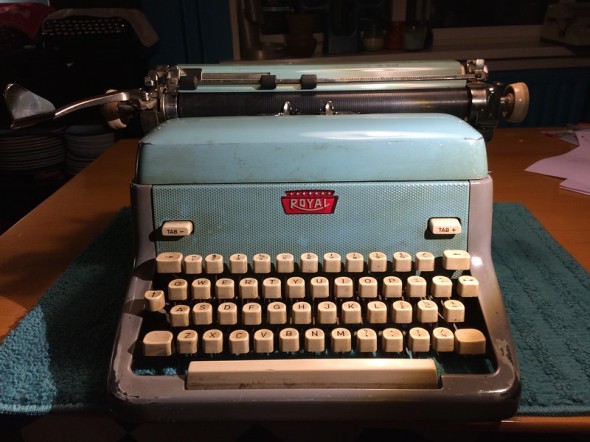

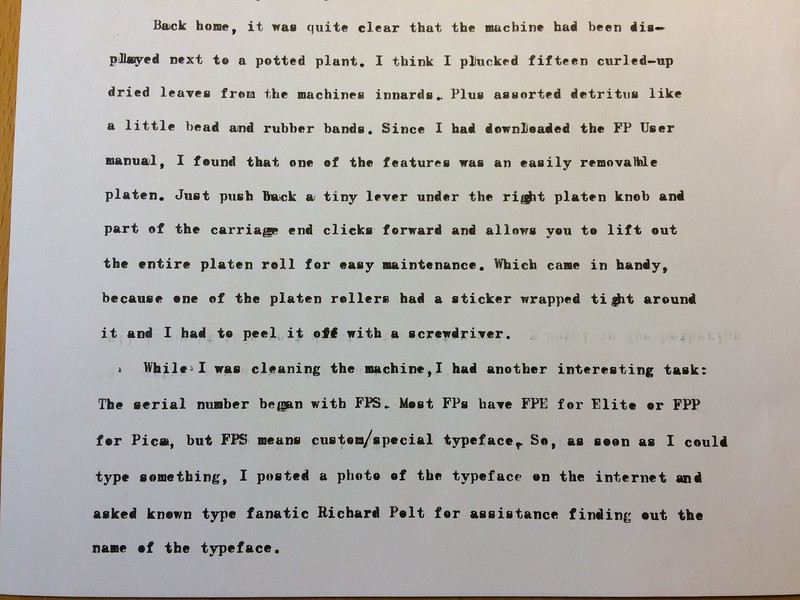

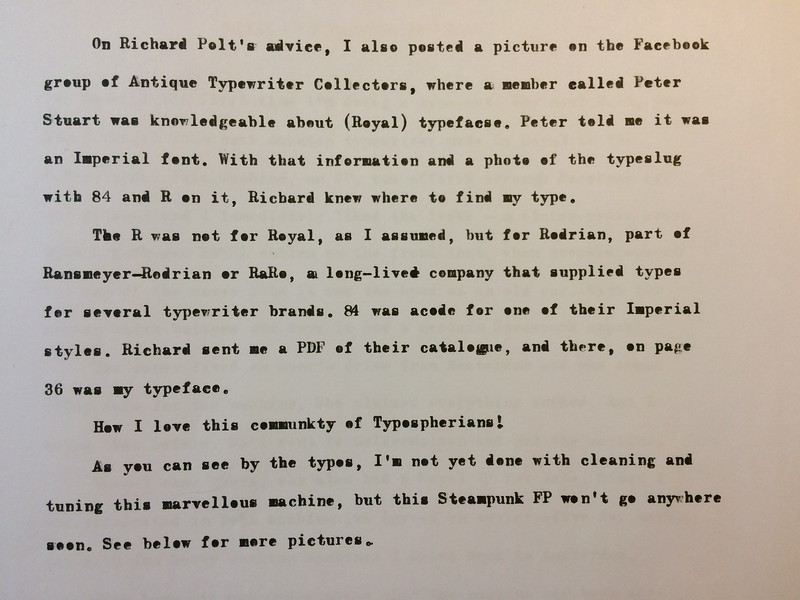

Typecast: My Royal FP – Steampunk

Posted: December 16, 2018 Filed under: Typecast, Typewriters, Uncategorized, Writing | Tags: Elite, Imperial, Ransmeyer, Richard Polt, Rodrian, Royal FP, Steampunk, Typecast, Typeface, typewriter 2 Comments

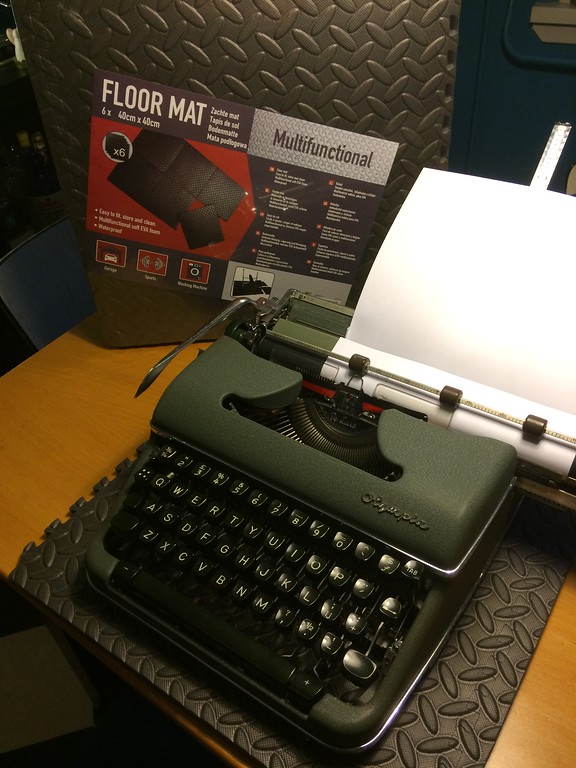

Typewriter Pad Alternative

Posted: December 12, 2018 Filed under: popular, review, Typewriters, Uncategorized, Writing | Tags: alternative, desktop, EVA, foam, industrial, manual typewriter, Olympia, Remington, solution, tile, typewriter, typewriter pad, Underwood Leave a commentOne thing that annoys most current typewriter enthusiasts is the availability of typewriter accessories, or rather, the lack thereof.

Tipp-Ex white-out paper and correction fluid is virtually impossible to find, silk black/red ink ribbons have to ordered at the office supply store (because they rarely stock them), typewriter erasers are thin on the ground, and — of course — typewriter pads have gone the way of the dinosaur.

Typewriter pads serve multiple functions at the same time. They protect your desk, they provide an anti-slip surface so the typewriter doesn’t skid all over your polished desk, and they dampen the vibration (and the noise!) of your typewriter.

Since the original typewriter pads are no longer made and the commercial alternatives are not very cheap (I think 12-24 euro for a single pad is expensive), I experimented with all kinds of pads, from cork placemats from a cooking store (for underneath hot pots) to all kinds of rug runners and anti-slip bath mats. Some didn’t provide enough anti-slip, others were too soft or too thin.

I didn’t try the ‘cutting up a yoga mat’ idea, because good yoga or pilates mats aren’t cheap, but that last suggestion did give me a better idea.

Hardware stores often sell ultralight foam tiles that have jigsaw sides to join together in a large floor mat that you can use as in your garage or tool shed, as a gym mat or even under a washing machine to dampen the vibrations. Sold in packages of six squares, a single tile is often 40×40 centimeters, big enough for an Olympia SG-1 or similar desktop typewriter, so it can also easily support a smaller portable machine like this SM-4.

Every package has strips to cover the jigsaw sides and if the floor mat is too large for your taste, you can easily cut them down to size. They’re often available in a variety of colours (although I’d go with black), they are anti-slip, hard enough to support your typewriter, but soft enough to dampen the vibrations. Plus they’re cheap — a package containing six 40x40cm EVA foam tiles will cost you about 6-10 euro — and since they’re meant for work spaces they can handle an awful lot of abuse, so they will last very, very long. And I think they also look pretty cool/rad/industrial under your typewriter.